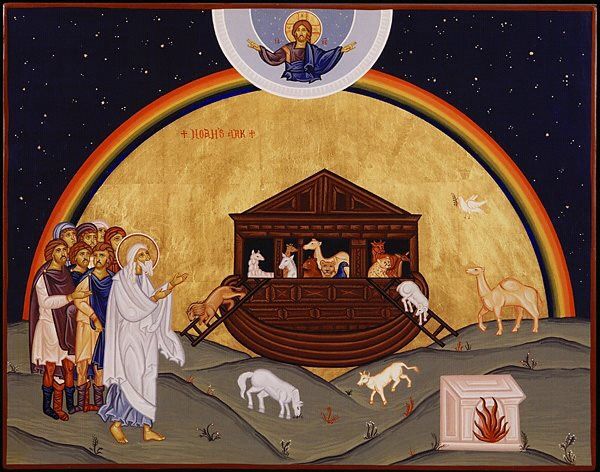

Noah, the Prophet, and the Word of God

“You search the Scriptures, for in them you think you have eternal life; and these are they which testify of Me. But you are not willing to come to Me that you may have life.

“I do not receive honor from men. But I know you, that you do not have the love of God in you. I have come in My Father’s name, and you do not receive Me; if another comes in his own name, him you will receive. How can you believe, who receive honor from one another, and do not seek the honor that comes from the only God? Do not think that I shall accuse you to the Father; there is one who accuses you—Moses, in whom you trust. For if you believed Moses, you would believe Me; for he wrote about Me. But if you do not believe his writings, how will you believe My words?” (The Gospel According to St. John 5:39-47).

During the holidays, some family members came to visit and meet Nikiforos. It was a nice couple of days where people I do not get to see very often made the trek to the desert to meet their newest family member. During this time, one family member and I began speaking about the Flood narrative in the Bible, to which they stated that they believed that was an interpolation from the Sumerian flood story: the Eridu Genesis.

This perspective rests on modern scholarly dating which places the Sumerian flood account earlier than the Genesis narrative and therefore assumes literary dependance. The essay that follows does not hinge on the accuracy of these dating models; however, it is worth noting that the controversy—and the belief—arises from this chronological assumption rather than from textual similarities alone.1

This was scandalizing for me, not so much because someone who professes to believe in the Bible would also think that there are some stories in the Bible which did not come from our tradition, but more than that, what that actually does to our tradition. It breaks the paradigm in such a way that the worldview ultimately does not matter.

For example, say you’re a scientific materialist who also believes that miracles have occurred in history, for instance, the miracles of Jesus Christ in the first century. You, as a scientific materialist, believe these to be genuine miracles. OK—not only does this, ironically, make you a Cessationist—but this would be incongruent with your own worldview; it opens the doors to questions such as, Why these miracles and not others?

What I’m trying to show is that, not only for Christians, but all people have a priori paradigmatic commitments which cannot simply be yielded to the acceptance of things at variance with their own worldview without collapsing it.

To return, the claim that “Noah” is a figure from Mesopotamian myth is precisely the kind of claim which—while being assumed and not demonstrated—collapses the Biblical worldview. It’s not a neutral statement to claim that Noah is, literally, “Ziusudra.”

It is not logical to state the following:

There was an event and because one person described the event earlier than another, we can infer that the later description is actually a derivative of the earlier recording. Not to mention that the Bible itself accounts for why there would be various descriptions and stories describing the same event, found only a few chapters after the Flood at the Tower of Babel.2

The memory of the Flood was preserved by the cultural diaspora following Babel in different tongues. This in itself explains the different flood stories from within the worldview rather than opening the paradigm to hypothetical interpolation.3

St. John Chrysostom writes of the Prophet Moses as receiving revelation in reverse, that is, he was blessed to see the events unfolding as they did by his relationship with God and the purity of his nous. Therefore, we know the witness of Genesis is true, not because Moses was there at the creation of the world, but because he knew God—he stood before Him. Moses is not simply the author of the Pentateuch; he is the God-seer, and this revelatory account of Genesis is meant to help us see God, too.

This is an exemplary case of how biblical criticism actively undermines the Christian Faith; it’s not because the Christian Faith is primitive or incoherent, but becomes incoherent when post-Enlightenment literary criticism is applied to our sacred scriptures. So, let’s just look at how this distorts the entire paradigm:

If the Prophet Moses is the author of the Pentateuch, which he is traditionally understood to be, and the Genesis account borrows from other cultural narratives, then divine revelation has nothing to do with his authorship and the text itself isn’t inspired. Yet, this opens the door to the above questions offered to the scientific materialist: Why are these accounts inspired and not others?

And worse, for some Christians in our modern day, the questions become akin to: Couldn’t they all be allegory and still be the backbone of our Faith?

No, they cannot.

The Old Testament is a genealogical catalogue at its core. It traces Christ through the generations and is an unfolding of God’s revelation through time culminating in the Incarnation of the Word of God.

We wouldn’t map our own genealogical roots and arbitrarily decide that one figure in our family trees suspiciously resembles another figure in a different family tree, thus deciding that our ancestor is a borrowed item from a separate genealogical map. That’s beyond illogical, yet many people feel that is exactly what they can do to Christ’s genealogy.

However, the significance of Noah in Christ’s genealogy cannot be overstated. Noah is the bridge between the antediluvian world and post-Flood humanity; he is the human element that marks the pivotal shift leading directly to the calling of Abraham and ultimately to Christ. If we reduce Noah to a borrowed mythological figure, then we create a rupture in the sacred chain of humanity, which culminates in the Incarnation. The Apostles saw this continuity (cf. Matt. 1:2-16; Lk. 3:23-38; I Pet. 3:20), with Christ explicitly connecting His coming to the days of Noah (cf. Lk. 17:26-27), indicating that Christ Himself saw the reality of his figure and his real participation in the unfolding revelation of God to His people.

The Old Testament, therefore, cannot be an analogy; it is not a collection of stories meant to demonstrate a moral mode of being. The Old Testament prophecies Christ and reveals God through His interactions with His people. It is, for us, a portrait of a people struggling to become perfect before God Himself comes to them to raise them to perfection in and through Him.

If we see the Scriptures as a puzzle slowly imaging Christ, then we can see that, by removing some pieces which we feel do not belong then we are distorting the very Image of the invisible God (cf. Col. 1:15). Thereby constraining God’s Incarnate intervention and striving against Him by forcing the invisible God to remain unknown to us. However, recognizing the invisible God imaged in the Son is demonstrable in the reading of the Scriptures and the Gospel. God’s revelation to the human heart is found in these hallowed pages; reading them is accompanied by a phenomenal transportation of some kind.

It is kind of like an elevation and being carried off to these eternal moments; as if one is both in the first century and at their prayer corner, somewhere in between; outside of time while being inside it. The words of the Scriptures, the Gospel, and the Epistles are icons depicting heavenly realities and revealing the Word of God. Though they are entrenched in time during the Second Temple Period, they transcend temporal boundaries, connecting the reader with something primordial and eternal.

Reading Scripture is a way for man to draw near to His God; to know Him, but to know Him in doing His Word, in following Him (cf. Jas. 1:22). This is because our philosophy is not abstract but grounded in the eternal Logos of God. He is true philosophy and wisdom. To know God is to experience Him, because He is a Person—we do not love abstractions nor do we worship worldly concepts like unity or peace, but we worship He Who is undivided Trinity and grants us His peace which suprasseth all understanding (cf. Phil. 4:7).

The world seeks to know about God, but in Christ we come to know God directly.

Yet, the knowledge of God is itself a gift, reflecting the very Personal nature of our God and encounter with Him. God, Who loves man and “desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (I Tim. 2:4). The knowledge of the truth isn’t found in syllogisms or comparative claims about religion, but, like the Prophet Moses, is in standing before God. We cannot coerce God to impart His knowledge and wisdom upon us; we don’t practice a legalistic faith, but one of love, therefore we approach God through His Word: reading the Scriptures, prayer, asceticism, and preparing ourselves for Communion. This is grounded in the spadework of our Faith, emptying ourselves of what is not of God: “the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life” (I Jn. 2:16).

In emptying ourselves, we become receptive to God’s grace, and in the gift of His indwelling Spirit we become more like God, re-likening the image within, which allows us to see Him clearly. It allows us to approach with boldness and, in partaking of His divine energies, we, in our finitude, partake of His eternality.

This asceticism is integral to how we approach the Scriptures. In preparing ourselves to receive God’s grace, this purifies the nous and cultivates a humble-mindedness that allows us to receive the text as it is—revelation, not as mere human literature. This is why the Fathers encourage us to continue reading the Scriptures, echoing Christ’s exhortation (cf. Jn. 5:39-47), because the spiritual development of man’s heart directly affects the revelation of God through the text.

We’re not called to memorize the Bible simply as a rote discipline, but to engage continuously with the unfolding revelation of Christ. When we approach the Bible without this understanding and discipline, then we risk falling into the modern temptation to read with reductionist eyes, not one being rendered by God.

Therefore, Orthodox Christianity is not either purely personal relationship with Christ nor is it purely prescriptions for the hope of eternal reward; it’s both/and the growing of self in Christ. The realization of the Kingdom of God is a process of deepening our understanding and our Faith predicated on the crucifixion of self, denying the self, and uprooting the passions through repentance and by God’s grace.

Justin Marler writes, “In a world that loves self-satisfaction, Christ’s message is a most difficult one. The teaching of the cross is in radical opposition to the wisdom of this world. While the world teaches us to use every means to prolong and enhance our life, Christ teaches us that to die to this world is to live eternally” (Youth of the Apocalypse, 78). Thus, to approach God is to take up our cross and follow Him, dying to ourselves daily rather than encountering Him full of ourselves, clinging to pride and possessions.

We ought not to be discouraged from clinging to the Faith that has been handed down to us by our Fathers and Christ’s Church; the temptation to accept such ideas as Noah is nothing more than a transliteration of Ziusudra then not only are we breaking away from the Gospel, but we are conforming to the wisdom of this world (cf. Rom. 12:2). When we allow biblical criticism to inform our Faith and influence our beliefs, then we are exchanging the truth for a lie (cf. Rom 1:25).

Ultimately, the problem becomes the slippery slope where, in compromising on one issue, we open the door to compromising on it all and collapsing the Scriptures into mere conjecture and analogy. This is a form of interpretive Nestorianism, separating Jesus from Christ, the Man from the Word. In so doing, the Bible no longer functions as an icon revealing the Word of God through the language but becomes exactly what scholars describe it as: a collection of different genres and texts compiled in a library that’s been preserved. No more and no less.

It comes down to one of the most important questions Christ asked His disciples: “Who do you say that I am?” (Matt. 16:15).

He is either merely a man, who inexplicably has no connection to His own lineage, or He is the very Logos of God Who Incarnated, entering into man’s finitude to grant us eternal life. Our response to this question is as telling about our prior commitments as it is a revelation of the disposition of our own hearts. What stands in radical opposition to the wisdom of this world is approaching the text empty, crucifying the mind and allowing the icons on the page to image the Word of God not to debate with Him or to reduce Him, but to be changed by Him. The power of returning daily to the Scriptures is a pattern depicting repentance: returning over and over to God, not because He’s gone anywhere, but because our eyes are slowly growing accustomed to seeing Him truly, face to Face.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ

- The hermeneutical principle privileging chronology arises out of the 18th and 19th centuries German biblical criticism movement. Specifically, through the work of Julius Wellhausen’s systematizing the “documentary hypothesis” which postulated that the Pentateuch was a compilation of fragmented writings from four hypothetical literary sources. Wellhausen’s work, alongside other post-Enlightenment biblical scholars of his time, assumed cultural evolution a la E.B. Tylor’s speculative development theory of religion.

These approaches did not merely analyze texts historically; they presupposed Tylor’s development model in which earlier traditions are religiously rudimentary and later ones more developed.

Later archaeological and philological discoveries thus did not create the derivative theory but confirmed what biblical critics already expected; the interpretation of artifacts was filtered through this lens rather than informing the lens itself. An earlier date was interpreted as source material while later dates were interpreted as derivative. ↩︎ - This argument does not depend on the accuracy of secular dating. It is intended to demonstrate that, even when such models are provisionally granted—while not being accepted by this author—the conclusion of cultural borrowing does not follow logically. ↩︎

- It is also worth noting that claims of cultural borrowing from Mesopotamian flood traditions rest on selective evidence. Numerous flood narratives exist among peoples with no demonstrable textual or cultural inheritance from Sumerian civilization. These include various African, Indigenous American, Australian, European, East Asian, and Oceanic traditions. Within an empiricist framework that prioritizes evidence, the widespread and independent appearance of flood narratives presents a difficulty that is often dismissed rather than addressed. The biblical account is inexplicably treated as derivative, while analogous accounts are relegated to myth—if they are accounted for at all—despite their global presence. ↩︎