A final reflective essay

This is an essay I wrote for my Mysticism: East and West course. It’s essentially a final exam. I spent a lot of time on it and thought it’d be good to share as an example of reorientation: moving beyond pure reason and abstraction, and taking steps toward re-enchantment.

Praxis is not opposed to or above theory, but theory without praxis is empty (cf. Jas. 2:26).

Here’s the prompt: “In this final assignment, I would like you consider more broadly what mysticism and mystical experience might mean to non-mystics. In their writings, mystics make both metaphysical and moral claims, about the (purportedly) true nature of reality, as well as the deep interconnections between all creatures.

“So, consider the following issues in your essay: If the rest of non-mystical humanity were to take the conclusions of the mystics seriously, what sorts of changes might we (as a human culture) make to our political and social worlds? For example, how might we change our educational system? Our criminal justice system? Our social media relations? Be sure to support your positions with reference to at least some of the materials that we have studied this semester.”

Mysticism as Praxis

Mysticism is about what one does; mystical vision is entered through praxis, not through perfect comprehension. In the Eastern Orthodox world, there’s a colloquial term for this: yaya-ology. This refers to the grandmother who lives faithfully and prayerfully yet may not be able to explain her faith via logical syllogisms or even know what a metaphysical principle is, but she embodies a mode of seeing rooted in participation. This reveals the essential challenge for the non-mystic: mysticism is not propositional, but a way of life. The mystic speaks from a cultivated vision, shaped by asceticism, prayer, and contemplation, and attempts to articulate what they see into words.

For non-mystical humanity to take these mystical claims seriously is not to adopt every metaphysical detail. That’s impossible. However, they do need to recognize that praxis precedes mystical knowledge, making a shared moral vision possible—one grounded in functional similarity—when society reorders Truth, Goodness, and Beauty toward their transcendental source.

However, before society can take mystical claims seriously, it must discern which mystics it means. Evelyn Underhill’s Christian-Platonism differs from Ibn Arabi’s non-duality, and both are distinct from the Buddhist denial of self. There is no society that can adopt every mystic’s metaphysical claims simultaneously, but it can recognize that each tradition describes a path that leads to genuine transformation.[1]

Though the transcendental categories are entrenched in Western thought, they cut across cultures, from Parmenides to Patanjali, from Aristotle to Aquinas. They provide a common grounding through which our political, educational, and social landscapes can reorient and be transformed when mystical claims are taken seriously.

While modernity’s naturalism describes the world very well, it cannot prescribe moral or ethical directives based on those descriptions; yet it is the mystics themselves who claim to see Reality as it is, as Evelyn Underhill defines Mysticism [as] the art of union with Reality. Underhill continues, differentiating the non-mystical worldview as a lens which sees things as they really are, not understanding how much is missed, how much of the world is revelatory and beautiful for those with “Eyes” to see.

To reiterate, mysticism is not a single, systematic theory or practice; it’s not a panacea that will fix every problem in society. What it can offer is a corrective lens when employed by the individuals within those institutions.

The political landscape of our modern world potentially becomes recoded by Goodness: as Goodness is increased in the social imagination, so a mystical anthropology might take root, softening the boundaries of political discourse. Goodness, attached to transcendent metaphysical claims emphasizes compassion over compulsion. Thus, political ideologies potentially soften, influenced by the Christian clarion call to service.

The Christian mystic, Bernard of Clairvaux, writes, “As for your neighbor whom you are obliged to love as yourself (Matt. 19:19): if you are to experience him as he is, you will actually experience him only as you do yourself: he is what you are,” reflecting the Patristic view that to love one’s neighbor is to be united with him. When your neighbor is, truly, you—when there is an emphasis on the ontological interconnectedness of humanity—then economic theory and harmful policy-making could be corrected, fostering a political orientation that looks beyond power distribution and class struggle.

Where non-mystical humanity flattens the Good into an immanent moralism, normative claims lose their transformative power and function purely as societal regulation. A system built on compulsion rather than compassion works against the mystical view of ethics as integral to a person’s full development. When normative claims are connected to the transcendent, it opens a channel of transformation to the aspirant through participation in the Divine.

The mystical disposition would be one of service, grounded in actionable love; love that corresponds to the self-emptying of the Christian Trinity. Thus, love wouldn’t be about preference or convenience but would be transcendent and indiscriminate.

This reorientation of Goodness flows downstream of politics, reshaping the juridical imagination, where justice becomes Goodness applied to societal misconduct. The modern criminal justice system often falls into procedural exercises that risk becoming histrionic and retributive, at variance with rehabilitation. Drawing from the Dhammapada, the judicial landscape might shift by acknowledging that “evil” is an addiction emerging from attachment and delusion.

Recast through this disposition, restoration becomes the priority. This is not to excuse heinous crimes, but to allow offenders and victims to recognize their interconnectedness, revealing that the transgressions done against one is a transgression against all; contributions to the suffering of the world ripple out and take on cosmic dimensions.

Goodness, then, concerns right relation, whereas Truth concerns right understanding; therefore, this reorientation transforms epistemology, unfolding from an education system grounded in metaphysical transcendence. Truth, filtered through the mystical lens isn’t then about being “right” but embodying Reality.

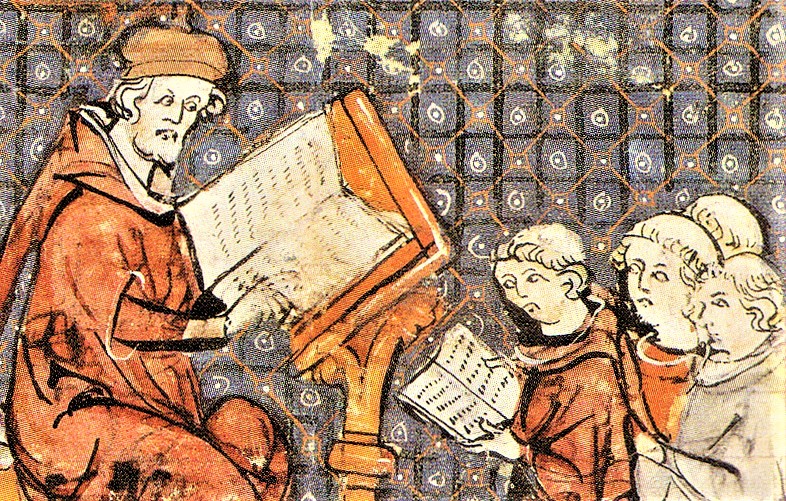

The educational system, then, becomes a gymnasium teaching the practice of Being. Instructors would echo Ibn Arabi caution of propositional truth: “He who seeks to know the Reality through theoretical speculation is flogging a dead horse.” Abstract and theoretical knowledge has its place, and modern technological advancement has done well to implement theory into design, but Truth transcends abstract philosophy.

A mystical approach to education prioritizes the formation of the student’s inner world over the input of information. A fitting model is a pedagogy focused on contemplation, reflection, and virtue. In implementing the wisdom of the Dhammapada, students will learn that doing good is a daily practice, filling a large pot with water; at first it may not seem like doing anything at all, but they are benefitting incrementally in this character formation.

Zhuangzi’s Daoist philosophy supplements daily practice by developing epistemic skills and shedding a light on false certainty. He writes that all perspectives and opinions are subjective, that trying to be right is an assertion of one’s ego.

This underscores the importance of recognizing one’s own biases and paradigmatic blind spots while emphasizing Being: “Perfect is one who knows what comes from heaven and what comes from humans… First, one must be true; then there can be true knowledge.” Aligning with the Dao is the greatest virtue; it is more important than acquiring information or winning debates; that is not Truth. Truth is alignment with Reality.

The formation of the inner world, alignment with Truth, transforms how one perceives the outer world. For the mystic, this is Beauty, Modernity collapses Beauty into aestheticism, and when this occurs, consumerism becomes the fruit of this reduction. The world becomes a registry of classifications, labels, and commodities. The mystic, contrary to the consumerist lens, sees the world as a revelation of meaning.

From the mystical perspective, conspicuous consumption is not merely environmentally unsound; it deepens man’s ignorance. For a Buddhist, it strengthens attachment and perpetuates suffering. For the Sufi, it is a deviation from love, a deluded perception of reality; consumerism images ghaflah: a lack of awareness of one’s origin and forgetfulness of God.

A non-mystical, secular strategy for overcoming consumerism suggests Give a hoot, don’t pollute, whereas the mystic might exhort us to give away what we have because our neighbor’s life is ours. Basil the Great highlights this warning with awe-inspiring frankness: by withholding from the poor, we are committing murder. This is not hyperbolic rhetoric to make a point; he means what he says. If we take the mystics at their word—as Katz suggests—then we see Beauty points to actionable love.

Beauty connected with the transcendent reverses this reductionism; Beauty then becomes participation in the Beloved. Art, literature, and design possess ethical qualities, because they participate in revelation. Rumi’s exhortation, “Let the beauty we love be what we do,” points to how Beauty shapes character and opens one’s “Eyes.” Beauty as revelation is a call to embody what is made visible.

Modernity distorts Reality by fragmenting the transcendentals: turning Truth into facts, reducing Goodness into moralism, and flattening Beauty into aestheticism. Mystics refuse this disharmony, challenging these assumptions by claiming to know these realities directly. Reality—is not made up of cold, insular facts, functional moralism, or subjective beauty.

The art of union with Reality is a corrective lens for the non-mystical world; taking mystical claims seriously means acknowledging—not just the limits of reason—but that reason is not praxis, and praxis is mysticism. Becoming True, Good, and Beautiful is not reasonable, it’s actionable. And no theory will enable us to understand unless we begin walking the path, practicing the art of union, and developing “Eyes” to see.

Moral Realism

Update: My professor deducted two points because I didn’t say anything about how social media relations would change if non-mystical humanity were to start taking mystical conclusions seriously. So, I started thinking about this paper again and I realized something about what underlies the prompt. A most serious change that would occur is the re-introduction of moral realism to our society, because if praxis helps reveal Reality, then morality cannot be optional or relative. It must be ontological.

Moral realism is an ontological perspective highlighting the objectivity of morality and, thus, normative claims. The above reflection demonstrates how society might reorient if we once again pair the phenomenal world with transcendental reality; from an Orthodox perspective, we might consider the transcendental categories of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty as energies of God.

The energy-essence distinction is more complicated than the scope of this piece, but it refers to the fact that God’s essence is unknowable and unfathomable, but His energies are His actions and operations in the world—how He interacts within time and space—and these can be experienced by man.

His energies are uncreated, becoming actualized through man’s participation in the sacramental life of the Church, through contemplative and ascetic practices, and following God’s commandments. Therefore, moral realism underscores man’s capacity to be deified by God’s grace (His uncreated energies). This deification in Eastern Orthodoxy is called Theosis.

Though the transcendentals manifest differently, they all point to the same Triune God. Recognizing this underscores a pressing concern: when non-mystical humanity embraces secular thought and reductionist worldviews, the transcendentals are flattened, and moral and spiritual realities are darkened. It actively turns man away from God.

Moral realism, for me, is not a philosophical perspective but the very grounding of mystical claims and movement toward the Divine. To quote a previous paper on the normative claims of Christianity, Buddhism, Sufism, and Daoism, I wrote:

“The moral life of the religious practitioner and mystical aspirant is grounded in theological origin and teleological assumptions. Morality implies dichotomous movement, which the aspirant must direct themselves: turning away from movement contrary to their aspiration and embodying motion aimed toward Reality. While the aim toward Reality is narrow, contrary movement is comparatively nebulous.

“The moral life in Christianity, Sufism, Buddhism, and Daoism shares an apprehension of a narrow path and agree that movement away from the aspiration is diverse yet diverges conclusively from Reality. Though these traditions possess similar views of Reality itself, their distinct metaphysical assumptions underscore the variety of moral living as well as the consequences of departure.”

Thus, for the mystics (save Zhuangzi), morality is not only objective but also it is one of the fundamental ways one aligns oneself with the Divine. And to turn away from this course is to turn away from the Divine; Orthodoxy sees this as sin: an ontological distortion. Moral realism provides the path back to re-likening the image of God within us, whereas deviations from Truth, Goodness, and Beauty are turning away from God’s energies and participating in non-being, fragmentation, and noetic darkness.

In Orthodoxy, the blinding of one’s spiritual “Eyes”—or nous—leads to a collapse of personhood. Humanity becomes reduced to consumers, psychological profiles, and economic units. Mysticism itself is often pathologized, as in the late-70s work Mysticism: Spiritual Quest or Psychic Disorder? by the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. Its dubious conclusions drew a false equivalence between mystical phenomena and psychiatric disorders, like epilepsy and schizophrenia. Its existence reveals the tension between mysticism and non-mystical humanity, where the latter needs to draw boundaries and qualify anything that falls outside the paradigm of reason that it has constructed.

This matters for the study of religion because theories of religion and mysticism in the university system often rely on data that was compiled from similar assumptions which the authors of the above paper possessed. Not only that, but rationalizing spirituality often means presenting an abstract map of religiosity across cultures, and while this is a valid methodological approach, it frequently falls into a reductionist view of religious phenomena. This paradigmatic lens is often committed to explaining away religious and mystical experience as pathological or an irrational response to natural stimuli.

There may be compelling cross-cultural evidence that shows a uniform religious phenomenon, but phenomena doesn’t suggest metaphysical homogeneity; in fact, it doesn’t necessarily tell us anything about metaphysics at all.

However, after World War II, this secular, “scientific” alternative to religion’s moral realism rose to prominence, reshaping humanity’s understanding of sin, separation, and communion. Influenced by Freud, Rousseau, and the rationalistic Enlightenment project, society turned away from normative and metaphysical claims, focusing on the individual. This decoupling of the transcendentals from the Divine transformed deification into self-actualization, sin into dysfunction, and demonic influence into trauma.

The psychologizing of reality further moved man away from God and moral objectivity, reorienting man toward humanistic, therapeutic solutions to unhappiness and unfulfillment. The counterculture of the sixties embraced the self and emphasized egoic realization. While all these movements had a hand in shifting man toward an atomized self, the authority of psychology was legitimized through academic institutions pushing to replace the void left by the deracination of the transcendentals and morality.

We, as a society, were left with a meaning crisis (that we’re still in) that the field of psychology promised to provide a framework which allowed for individuals to access meaning through a personalized, relative pathway to fulfillment and happiness.

The vacuum that psychological and sociological functionalism filled, interestingly, reflects a modern shift toward the avoidance of suffering and desire for happiness, convenience, and comfort. This Epicurean turn reflects the ancient temptation to seek after well-being without God. The philosophical shift destroys salvation through reason and makes it attainable through human effort and cognitive ability. Yet rebranding the Babel-impulse as secular humanism and dismissing the metaphysical grounding—and thus the teleological function of normative claims—intensified this shift.

Such a humanistic departure dismisses the claims of mystics, undermining the ontological nature of morality and man himself. In opposing Divinity, flattening the transcendentals and pathologizing moral deviation, humanism is fundamentally anti-human. Thus, we are left with a humanist imperative: suffering is to be avoided, and comfort is better for the preservation of the species.

This highlights modern man’s implicit fear of discomfort; the relativism of morality reflects man’s desire never to be challenged on their worldview or actions; moral realism re-images a man that is called to become a person in Christ—to be forged through suffering as Dostoevsky’s writings profoundly emphasize.

For Dostoevsky, suffering is the gateway to compassion. Goodness, then, is attained and refined through confronting discomfort and suffering; and bearing our cross in it. Beauty is the struggle, highlighting the Christian’s direct participation in the life and suffering of Christ. This ontologically changes who we are by revealing who we are in Truth.

The modern rationalist paradigm not only relativizes morality, but reshapes the very institutions that claim to make a discipline of the spiritual. Modernity’s psychologizing of life undermines telos and renders moral objectivity unintelligible to the secular mind.

This is not a bug, but a feature.

The Modern Machine

Once an anthropology is institutionalized, it seeks technologies and philosophies that reinforce it in the public imagination.

Academia, whether intentionally or not, undermines religiosity and mystical experience by reducing spiritual traditions to sociological function and cognitive processes. While this may be the case sometimes, this exception seems to have become the rule. The reason for this is that academic power and perspectives are entrenched in abstract theorizing; it’s all speculation, which the Buddha decried as a distraction from the spadework of enlightenment.

An example of this is the university system talks about the benefits spiritual traditions claim are derived from meditation, yet there is no educational imperative to see whether that’s true or not. There is a directive to write an essay about the cross-cultural manifestation of meditation, but the ubiquity doesn’t seem to suggest that the practice may be essential. It has become a cultural artifact. Praxis itself has become a thing religious traditions and pre-modern cultures did because, well, they simply didn’t know about rationalism or economic progress.

It’s a challenge to read the speculations of these 19th and 20th century thinkers, who arrogantly presented their philosophical musings as hard scientific fact.

The reality is these thinkers are, for someone like Nietzsche, contemptible, because in their arrogant usurping and killing of God they pathetically held to Christian morality stripped of its transcendent justification. Without God, Christian morality is reinterpreted as prioritizing happiness and harm reduction. Nietzsche would eat the secularists clinging to such a Christian heresy because he saw, as did Dostoevsky, suffering and struggle as fundamental tools in the shaping of man, revealing who he truly is.

Modernity’s moral relativism and its psychologizing of reality are unconsciously working out the very ethical framework that it wants to destroy.

The psychological self remakes man in the image of his society; precisely why the inward turn of modernity supports cultural consumerism. The reduction of religiosity and flattening of transcendental categories. The de-spiritualization of participatory epistemology is what reshapes man into an economic unit who either produces or consumes.

Modernity tells us there is nothing beyond materialism. There is nothing beyond naturalism. And there is no way to participate in the energies of God, so it’s more worth your time to seek out happiness and comfort. These have become our new gods, which we serve by living lives with the self at the center.

Even religion often cannot resist institutional capture. Though the mystics challenge the assumptions made by modernity, many have been subsumed by the Machine.

Where Buddhism’s normative claims are dismissed and its practices are sanitized by corporate power and reinterpreted with productivity as the aim. Daoism is flattened to self-affirming, positive nihilism. Sufism becomes poetry. Christianity becomes sterilized, Christ becomes a mere man, and public pressures compel Christians to tolerate sin, thus implicitly rejecting its own tradition’s normative claims.

Religions that are not publicly disavowed can be co-opted by the Machine, becoming cogs keeping man susceptible to its institutional power. Even normative claims that once were actionable elements of direct participation in the Divine, have now been reinterpreted as secular prescriptions compelling man toward what Nietzsche called the morality of the herd: a slave morality that prizes safety, comfort, and equality above all else.

The slave morality emerges as the state and secular institutions, like psychology before them, begin filling the void left by the erosion and collapse of meaning. No longer encouraging moral realism as ontological pathways to Divine experience, but now normative claims become slogans encouraging societal compliance. A recent example of secular religiosity, inverting prescriptive claims to embolden corporate and state power, was seen during the lockdown; it’s seen as ideological purity in the public square, and corporate virtue signaling. These are all recent instances of this religious pattern.

When moral realism and the transcendentals are flattened and reduced to what the secular mind can comprehend, then they can be weaponized to make the secular mind compliant. The therapeutic self that values comfort and safety over suffering and struggle place their salvific hopes in whatever consumer culture offers. We have exchanged the truth claims made by those who have participated in the noumenal worlds for a reality curated by algorithms and corporate power, enflaming in us the worship of self and dampening actionable love facing outward. This logic reaches its culmination in social media: the technological embodiment of societal fragmentation.

The flattening of the human experience and the love of many growing cold (cf. Matt. 24:12) finds its most immediate expression in social media and the algorithm: the central nervous system of the Machine. Social media relations reflect the devaluation of reality present in aestheticism, taken to the nth degree. Where aestheticism flattens reality to mere object, social media reinforces this compression through its very means of transmission. It relates information and reality through a flat, dark screen which, when turned off, reflects the image of its user. It is not so subtly informing us that we are, essentially, the commodity.

This is the logical end result of utilitarian ethics and rationalist paradigms. When societal pressures erode the man’s connection to the Divine, then man is uprooted from his cause, redirected from his telos, and redrawn as a consumer who is a hollow shell, no longer filling his soul with heavenly experiences, but refills the well of his heart with objects and identity qualifiers which aestheticism has extracted all intrinsic value from.

We become malleable agents responding to preference, stimuli, and a desire for comfort. We are purified of our personhood and left to fall into arguments online in between binging on the latest consumer product and IP. We’re infantilized by corporate power that has slowly infected political power for centuries.

Where once Dostoevsky decried the eradication of the Christian God while professing Christian values now… It does not even appear we exhibit even the remnant of Nietzsche’s shadow of God hanging over a Europe that killed Him. The world we inhabit falls more into line with Prince Myshkin’s observation:

“People back then were not at all the same sort of people we are now, not the same breed as now, in our time, really, like a different species… At that time people were somehow of one idea, while now they’re more nervous, more developed, sensitive, somehow of two or three ideas at once… today’s man is broader—and, I swear, that’s what keeps him from being such a monolithic man as in those times” (The Idiot 523).

This is essentially the difficulty of diagnosing the therapeutic man, by embracing a psychologized self, man has embraced fragmentation; in clinging to rational compartmentalization, man’s many aspects become atomized. While the European atheist did not truly understand what he was doing when he championed the sword of the Enlightenment atop the throne of God, man now… is Legion.

Social media and algorithmic curation, funneling us from one fifteen-second-short about discourse in the world of stand-up to a twelve-minute-long essay about Marxist theory to an amazon Wishlist to a Steam library to a message board discussing a tragedy that happened five minutes ago in a country that we barely recognize diminishing our memory even of our own lives.

The obscuring of self by algorithmic curation and ideological, corporate capture undermines even the humanistic temptation toward self-divinization. We then idolize a simulacrum of self. It’s a copy of a copy of a copy, further obscuring the reality of Self and Reality itself. The image of man is distorted under constant commodification.

Modern man isn’t plagued by two or three ideas—we’re inundated by every idea. How can we expect non-mystical humanity to start taking mystics claims seriously unless we begin to see that being human really is: committing to a singular life, cultivating virtue, communing with God and neighbor; “to aspire to live quietly, and to mind your own affairs, and to work with your hands, as we instructed you, so that you may walk properly before outsiders and be dependent on no one” (I Thess. 4:11-12).

Returning to the Divine: Praxis, Moral Realism, and Orthodoxy

Christ tells us that if we love Him, we will keep His commandments (cf. Jn. 14:15). Thus, moral realism becomes the antidote to modernity’s relativism; by treating the normative claims made by the mystics seriously, non-mystical humanity will see what theory cannot map: Reality. Praxis is fundamental. It heals the nous, restores spiritual sight, and reorients man toward the Divine.

All of this clarifies that, while these religious traditions appear functionally similar through their normative claims, they offer a diagnosis of the problem where Orthodox Christianity offers healing. The nous within man is healed by participation in God’s energies; it’s not healed by reason alone, logic, or nirvana.

Moral realism, in this way, enables the image of God within man to commune with the Personal Triune God, pairing normative claims to the transcendental energies of God. This isn’t something man wills into being. It is a reorientation toward He Who is always present, inviting us the knowledge of Him through direct participation.

This cannot be achieved through consumerism, aestheticism, or secular morality. Salvation is found through directly experiencing God in Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. This doesn’t exist in a simulation. It exists in taking the normative claims of the mystics seriously. It exists in the Orthodox Church and her prescriptions, where we unite—not with abstract theory, not relative moralism, not preferential aesthetics—with the Living God.

As a yaya once said: You don’t change Church, Church changes you.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ

[1] The implications of assuming drug-induced mystical states are genuine and ought to be taken seriously is a Pandora’s box.