Love is an Apocalypse

“I had heard a good deal about him before and, among other things, that he was an atheist. He’s really a very learned man, and I was glad to be talking with a true scholar… He doesn’t believe in God. Only one thing struck me: it was as if that was not at all what he was talking about all the while, and it struck me precisely because before, too, however many unbelievers I’ve met, however many books I’ve read on the subject, it has always seemed to me that they were talking or writing books that were not at all about that, though it looked as if it was about that…

“The essence of religious feeling doesn’t fit in with any reasoning, with any crimes and trespasses, or with any atheisms; there’s something else here that’s not that, and it will eternally be not that; there’s something in it that atheisms will eternally glance off, and they will eternally be talking not about that… God be with you” (The Idiot 219, 221).

I’ve been re-reading The Idiot with my son, Nikiforos, since his birth. As he la in the hospital bassinet, crying, unsure of the world, Prince Myshkin was arriving in Russia, fresh from his own hospital stay in Switzerland. The steady beats of the monitor and strong first breaths of Niki were coupled with the trains humming through Russia and the prince’s introduction to an unrecognizable Petersburg.

What became clear with these two arrivals—my son’s and Myshkin’s—was that they were apocalyptic, an unveiling of truth. Eternity breaking into the mundane, revealing the axis of reality is love, not rationalism. The heights of space do not reflect cold, analytical reason but image the mystery of God’s fathomless love, the very love that we are born to experience.

Reading Dostoevsky with my newborn unfurled a question: Does Christ-like love and compassion even make sense, or does it look merely like idiocy to the wisdom of the decaying world?

Prince Myshkin, who is a “positively beautiful man,” has a striking effect on those around him.

The first time I read this book it boiled my blood seeing the way in which the characters engaged with our hero, Prince Myshkin, but the more time I’ve had away from it the more I realize it simply was due to their complete disarmament around him. His presence demanded a response from those around him. Sometimes it was a softening and at other times, even in the blink of an eye, the characters would turn on him. Mocking and deriding his not acting according to their standards, according to the world that they inhabited.

To them, insanity was acting with compassion, kenotic (self-emptying) love, regardless of the consequences. But that’s the thing about Dostoevsky: he exposes our misconceptions about what is “sane”, logical, and meaningful. His writing makes the reader confront the limits of logic and even the irrationality of pure rationality.

He presciently foresaw a world of cold, analytical engagement that deracinated humanity; reason reduces religiosity to cognitive processes and evolutionary relics of a bygone, archaic past. Yet, it is reason that also has led to the unmaking of man by modernity; the primacy of the intellect has made us forget we are relational creatures, that we embody this world, that we are unique amidst the unfolding expanse of time and space.

The analytic mind has made man go hollow; far from the firelink shrine of the heart, he moves through this world dimly. Present, but empty, devouring life rather than receiving it—a stranger to himself and to the world.

Prince Myshkin stands as a figure that logic cannot explain. Reason alone cannot comprehend Alyosha or Elder Zosima from The Brothers Karamazov: “For the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness cannot comprehend it” (Jn. 1:5).

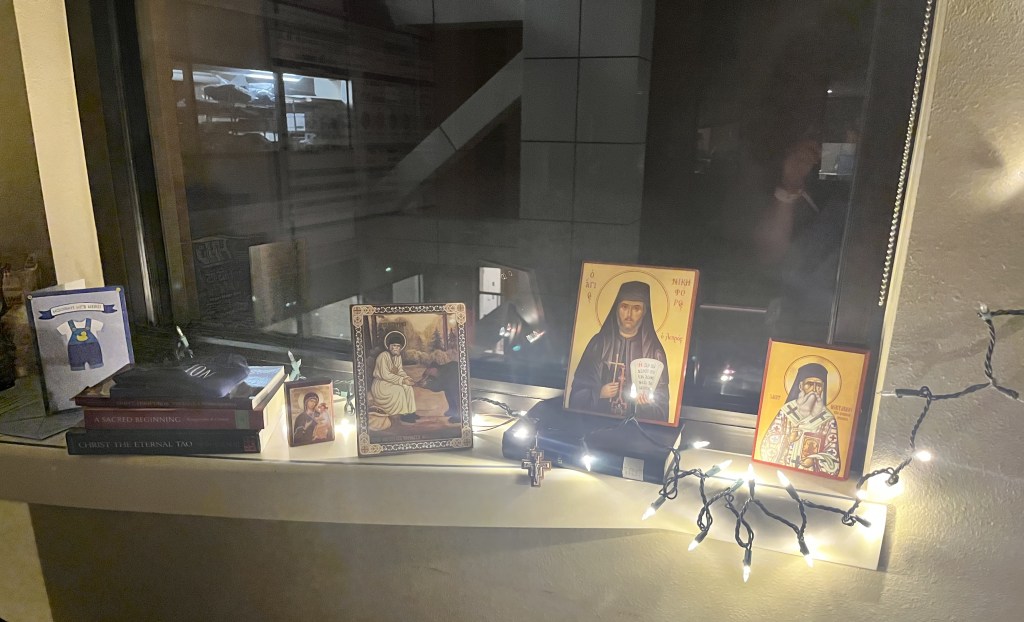

A lot of my personal feelings about reason, logic, and materialist theories regarding faith, mysticism, religiosity, and even Reality have been influenced by this year’s coursework. If you read enough Freud, Tyler, and Bertrand Russell, especially late at night when the birds aren’t singing, the echoes of a baby I want to dance with ring through the house, and a prayer corner’s haze feels like eternity knocking at the door, disenchantment creeps in like an invasive species—yet the icons on the wall and the noise of my family in the next room renew in my soul what it really means to be human. It’s something no theory can capture, like Karl Marx attempting to explain prayer using economic models.

There is something inherent in how these thinkers see the world that is so deeply unsatisfactory one truly understands what Prince Myshkin means when he says, “it has always seemed to me that they were talking or writing books that were not at all about that, though it looked as if it was about that…”

The materialist theories about religion we’ve read in my course have their (many) faults, but they read as particularly void against the rapturous feeling I get watching Nikiforos wave his arms convulsively, desperate to be held.

And while it’s fun to critique these thinkers’ presuppositions and conclusions, The Idiot reminds us that every moment is an infinite treasure, an eternal mystery. As Makar Ivanovich, in The Adolescent, says to his son,

“Everything is a mystery, my friend, there is God’s mystery in everything. Every tree, every blade of grass contains this same mystery. Whether it’s a small bird singing or the whole host of stars shining in the sky at night—it’s all one mystery, the same one. And the greatest mystery of all is that awaits the human soul in the other world” (The Adolescent 355).

I want Nikiforos to know this, too, that life is meant for repentance and to walk in love. I don’t want him to think that we need to know everything: “Knowledge puffs up, but love edifies. And if anyone thinks that he knows anything, he knows nothing yet as he ought to know. But if anyone loves God, this one is known by Him” (I Cor. 8:1-3).

Life is too short to argue with 19th century anthropologists.

I don’t think it’s valuable to be intelligent or rational if one does not know love (though we will look at how logic in modernity fails). Cold reason keeps us self-enclosed. It guards our egos against transformation. In the short time we’ve spent together, my son has taught me is that self-denial is not a logical exercise; ego-death is not reasonable. They are reflective of Christ’s love for man.

The Logos, the ordering principle behind all things, sustaining and governing, is beyond logic, language, and image; yet He became Incarnate and dwelt among us. The Son of God became the Son of Man so that the sons of men might become sons of God. My wife and I get to experience love becoming incarnate in our son, and this fundamentally changes the way reality is ordered.

And Reality is incarnate!

Dostoevsky has been a guide these past nine months, and now Nikiforos takes my hand with our Russian prophet as our companion, deepening the understanding that reason won’t change minds; logic does not win converts. What transforms us are the cries of a newborn, needing our help; man is unlike most creatures in that when we are born, we need another. We are not islands, and salvation is impossible alone. The later Christianities that emerged in the wake of the printing press and intellectual faith reduced a living faith to a propositional one, losing the profundity, the scandal, of the Incarnation.

I’ll say something I feel is blasphemous in this day and age: I don’t care about being smart. I don’t care about being intelligent; I can sit here every week talking about metaphysics, ontology, paradigms, etc. (and I still will), but where the intellect does not dare to tread… That’s where I want to go. Lao Tzu wrote: “In pursuit of knowledge, everyday something is acquired. In pursuit of Tao, everyday something is dropped” (Dao De Ching 48).

Prince Myshkin does not care about how he is perceived; he simply loves and extends the arm of friendship to even his most base enemies. Just like the prince, Nikiforos’ presence makes the affairs of this chaotic world dissolve; he reveals an ineffable love simply by being. All that matters is Christ, my wife, and him.

I can’t give to people halfway across the world, but I can give to my family, I can give to my community, and I can love even those who would mock my Faith. This modern world wants us to forget about Faith, it convinces us that identity is self-authoritative, that community is optional, that the Church stifles freedom. This is not true, and it is hurting our souls. It is distorting the image of God within every man, woman, and child.

It’s not a time to be reasonable. It is not a time to be logical. It’s not time to be ‘sane’. “Behold, now is the favorable time; behold, now is the day of salvation” (II Cor. 6:2). This means letting go of the primacy of the intellect and descending into the heart, not as metaphor or therapeutic, but truly rooting in the heart.

My patron is St. Nektarios. He was a lifelong learner, incredibly intelligent, and a wonderful pedagogue. But he didn’t accumulate knowledge to argue; he learned more about God to love Him better. So, this isn’t anti-intellectual, by any means, but about priorities.

My son has come into the world, and that’s changed everything; he began as a wee blueberry, swimming in his mother’s womb, and now he rests in my arms. He looks around, eyes flitting from here to there; he cries, and it sounds like a little steam whistle; he sucks on your finger and yawns, and he’s Beautiful. He’s made me grow up in the short time he’s been here. He’s made me forget myself, and he’s captivated our family.

Like Prince Myshkin, Nikiforos disarms everyone who encounters him, softening their hearts, and revealing love—transcending reason.

The prince, in answering Rogozhin’s question of whether he believes in God, talks about a mother seeing her nursing baby’s first smile:

“’It’s just that a mother rejoices,’ she says, ‘when she notices her baby’s first smile, the same as God rejoices each time he looks down from heaven and sees a sinner standing before him and praying with all his heart.’ The woman said that to me, in almost those words, and it was such a deep, such a subtle and truly religious thought, a thought that all at once expressed the whole essence of Christianity, that is, the whole idea of God as our own father, and that God rejoices over man as a father over his own child—the main thought of Christ” (The Idiot 221).

I cannot fathom this love. I can’t rationalize it. I can only open myself to it and try, by God’s grace, to live it. If this looks like foolishness to the wisdom of this world, then so be it! Let it be foolishness; I’d rather be seen as a simpleton, laughing with my baby and trusting completely in Christ, than a learned man, keeping all things at a distance.

It may be foolish to the world, but it’s true that Christ reconciles all things—Niki, my wife, and my own heart—to Himself (cf. Col. 1:20). He is closer to us than we can even be to each other.

Everything is a mystery, my friend, there is God’s mystery in everything. Every tree, every blade of grass contains this same mystery. Whether it’s a small bird singing or the whole host of stars shining in the sky at night—it’s all one mystery. The Incarnation is born in every heart, holding all things together.

And thanks to Dostoevsky and Nikiforos, I’m seeing it for the first time. By God’s grace, I’ll live it, baby in arm, with our Russian companion, seeing the world as it is: Incarnate, alive, and Beautiful.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ