Lazarus Saturday; Palm Sunday

Epistles: Heb. 12:28-29; 13:1-8 — Phil. 4:4-9

Gospels: Jn. 11:1-45 — Jn. 12:1-18

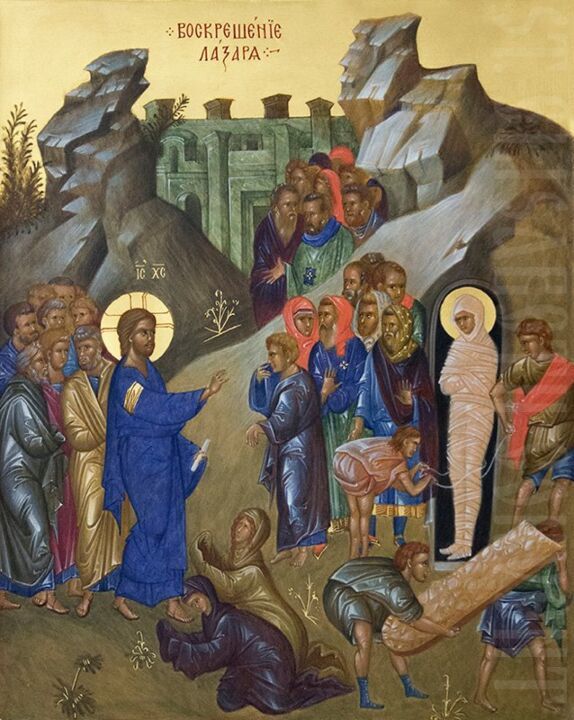

The raising of Lazarus is the Gospel in miniature.

It reveals Christ coming us, rolling away the stone covering our hearts—our nous—calling us to life, to become children of God (cf. Jn. 1:12). This event prefigures His Resurrection, His conquering of death by death, unveiling His dominion over all things, even over the outer darkness, which is illumined by the light of His countenance.

But this is not merely a demonstration of divine power. It is an icon of Christ’s self-emptying love. Many in His time, like those shouting “Hosanna!” during His triumphal entry into Jerusalem, misunderstood His mission. We often do the same. The Incarnation—God taking flesh—is not about spectacle, but love: a love that heals, restores, and raises us.

This Lent, that reality has become almost indescribable to me. The fast has opened my heart not to new insight, but to silence. The more I have contemplated what this Gospel shows us, the more I’ve realized how little I have to say. This is not because there is nothing to say, but because no words can truly contain the weight of such divine humility and love. We are not spectators here. We are participants. Communicants. And as much as I long to speak like the saints I admire, sometimes words simply fall short.

Love must be for another to be real. And in this raising of His friend, Christ reveals that love is the very foundation of being. To exist is to be in communion, and to be in communion is to pour oneself out for another. When the Evangelist writes that “God is love” (I Jn. 4:8), he speaks of this very reality: love is not a feeling, but the relational substance of all things. This is the love Christ offers freely. Lazarus’ resurrection is an image of sinners called out of darkness to dwell with God.

But how can words possibly illustrate the sheer magnitude of Christ’s limitless love and humility? I’ve tried, and yet each time I try to write, it’s like trying to describe the pain of my TMJ to someone who has never felt it—a pain that isolates, that feels like its own tomb. And yet, even in that affliction, I’ve found myself clinging to the belief that Christ is near. That He knows. That He weeps.

We live in a world where our tombs have become our homes. A simulated life—through screens, ideologies, and curated personas—has become normal. We walk, but spiritually we are fragmented. Social media, metrics, polemics, economic obsession—these are the garments of distraction. The discourse changes, but the pattern remains: it draws us away from life. And life is Christ, “for in Him we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Many of our tombs began as lifelines. They gave comfort once but calcified into places of isolation. They became sepulchers. But Christ, as He came to Lazarus, comes to each of us, calling us out of our self-made graves, reminding us that we were made for more than this deadened walk through the world. This resurrection is not just moral or emotional, but ontological. In it, we glimpse our return to the divine order written into all creation.

This passage resonates with St. Maximus the Confessor’s teaching on the logoi—the inner essences of all created things—which have their origin in the eternal Logos. Christ’s purpose was to bring everything to consummation. He is our beginning and our end, and anything that diverts us from Him is not life, but a distortion of it.

The logoi in us long to return to Him, yet the passions and demons attempt to thwart this return, leading us, by our own volition to exchange what is better, our true being, for what is worse: non-being.[1] In recent times, they manifest through mechanisms like social media, which invite us to become objects of our own desire. We brand ourselves, project identities, and become entombed in digital simulations.

It is not enough to understand Lazarus’ resurrection historically—it must confront us personally. Scripture is not only read; it reads us. It reveals our hearts, either hardening or softening them.[2]

Deep calls to deep (Ps. 41:8 LXX). Our essence longs for God, even if our choices betray this longing. When we surrender to the material world to define us, we give ourselves over to the machine. Identity becomes a project of power and control. But true power—the power given by God—is the power to become His child. The logoi in us are diverse in their expression, but united in their orientation: they seek His glory, not the glory of men.

This is the kenotic love that generates and sustains all creation. The raising of Lazarus and Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem fixes His work in time, yet His presence makes them eternally present. He is always entering our suffering. He is always going to the Cross. His love is His energy—limitless, always relational. Self-love, as the mother of all evils, is finite and darkened, incapable of true knowledge.[3] It is communion that makes the person known. Without communion, we isolate ourselves as individuals, clinging to ever-shifting identities built on temporal feelings and metrics.

Repentance emerges when our eyes open to how our thoughts, words, and deeds affect others. It is not merely turning inward in guilt but opening outward in love. Repentance is the renunciation of our self-directed chaos and a movement toward coherence and communion.

And yet, some of us are still in the tomb. Still suffering. Still aching to stand. But the amazing thing—the thing that grounds this story in the immeasurable self-giving love of God—is that Christ does not merely call from outside the grave. He goes in. He descends. He rides a donkey toward crucifixion, not just to redeem sin, but to be with us in our pain.

He rides to those like me who, while alive, are falling apart on a daily basis, clinging to His word. He touches even this pain with His divine presence so that even in my affliction I know He is with me.

St. Isaac the Syrian writes:

“He who senses his sins is greater than he who raises the dead with his prayer… To him who knows himself is given the knowledge of all things.”

This is the glory of the Incarnation: God took on flesh, united divinity with humanity without confusion, and revealed in Himself “all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Col. 2:3). He gave us the path to self-knowledge through repentance.

After his resurrection, Lazarus dines with the Lord. Martha serves. The house becomes an icon of the Church, showing us why Christ came—to be with us, and to give Himself for us.

He calls each of us by name. He invites us not only to come forth, but to enter His Church, to partake of the Mystical Supper, to be transformed in Him. The raising of Lazarus and the triumphal entry are both marked by meals. Communion is not an isolated event, but a continual reality: God saves us and sits with us.

Yet He does not ask this of us without asking us to do likewise. As St. Paul exhorts:

“Present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God, which is your reasonable service. And do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is that good and acceptable and perfect will of God” (Rom. 12:1–2).

That renewal is repentance—a participation in Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection. It is a putting off of the old man (cf. Eph. 4:22), the rolling away of the stone. It is approaching God not out of presumption, but in humility, receiving what the world cannot give: Himself.

Faith is not assent to propositions. It is stepping toward Being when Christ calls. The Lord calls because He desires to abide in us, as a consuming fire (Heb. 12:29), burning away the passions and filling the heart with His light. He enters Jerusalem. He enters the tomb. And He enters our hearts—if we allow the stone to be rolled away.

But even this is not the end.

There are times when, despite everything, we still feel the weight of the stone. The grief lingers. The affliction remains. The miracle does not always come on our timetable. Yet the Gospel does not promise us instant relief. It promises God Himself. He waits with us. He weeps with us. He shares in our suffering, not to remove it prematurely, but to transfigure it.

This is the heart of our hope—not just that someone raised Lazarus, but that someone will raise us, along with all creation. That even the futility we experience now is not in vain. That our sighs, our groans, our restless yearning for wholeness, are already prayer.

As St. Paul writes:

“For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us. For the creation waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed… And not only that, but we also who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, eagerly waiting for the adoption, the redemption of our body” (Rom. 8:18–19, 23).

The tomb will open. The stone will be rolled away.

Until then, we wait, we repent, we serve, we dine with Him, and we listen for His voice calling us—again and again—to come forth.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ

[1] St. Maximus the Confessor, On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ, trans. Paul M. Bowers and Robert Louis Wilken (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 61.

[2] St. Maximos the Confessor, The Philokalia, Vol. 2, 116, St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarious of Corinth, eds., trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (New York: Faber and Faber, 1981).

[3] St. Thalassios the Libyan. The Philokalia, Vol. 2, 313, St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarious of Corinth, eds., trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, and Kallistos Ware (New York: Faber and Faber, 1981).