The Sunday of St. Mary of Egypt

Epistle: Hebrews 9:11-14

Gospel Mark 10:32-45

St. Anthony once told his disciples, Live as though you were not of this world, and you will have peace. His poignant words echo today, confronting a culture that roots identity in the shifting sands of the digital world and societal performance.

A while ago, I was speaking with a monk about living out the Christian life in today’s world. We both jokingly admitted that it would be easier to be martyred than living as a witness for Christ in this modern age—a world that distracts the soul and our spiritual life with endless scrolling, demanding visibility, and continuously feeds the ego with digital affirmation.

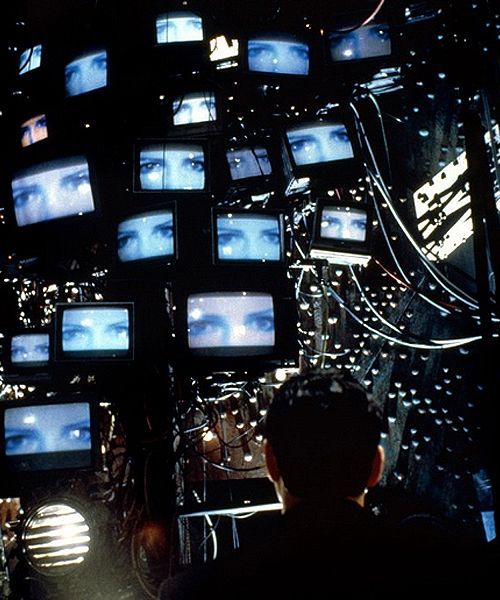

We live in a time where human identity is wrapped up in algorithms, platforms, and engagement metrics. We are constantly told likes and clicks define our value—reducing our human experience to feedback loops and simulations. While this has reached new absurdities in the postmodern world, with its xeroxed prestige and participation, it’s not a new temptation. This Sunday’s Gospel reminds us that living a life in Christ is not about content output or intellectual discourse. It’s not even about being seen, it’s about seeing Christ and living in such a way that others see Him in and through us.

As the Lenten season nears Jerusalem, the Sunday of St. Mary of Egypt grounds us; we confront the fact that, despite our striving for askesis, the goal isn’t checking off spiritual boxes—not boasting of prostrations or our fasting. The Gospel passage draws us into a renewed look at what Christianity is rather than what we want it to be.

The sons of Zebedee, Sts. James and John, approach Christ with a transactional mindset: “Do for us whatever we ask.” Their request exposes a temptation in all of us—to use God to become somebody, rather than receive in and through Him who we truly are. Today’s so-called secular age presents a problem: people practice Christianity in a way that seeks material blessings and hyper-individualism. I know, from my standing, it may seem slightly hypocritical to call this out, but when Christ becomes a vehicle for clicks and online discourse rather than the very Person Who provides the world Truth and in and through Him transforms us ontologically then we are simply engaging with the world as the world.

I have had to take a break from online spaces. The trend of Christian influencers, coupled with uncharitable online apologetics, leaves me somewhat disheartened. It has become clear that even within Orthodoxy, we’re often more influenced by the spirit of the times than the Spirit of God.

Disconnected from living the Gospel, we begin practicing a God-less Christianity—one that speaks of Christ often but relegates His Divinity to the background. This fragmented Christianity mimics the world rather than transfigures it. I write this as not someone above these temptations, but as someone who wrestles with them—wanting to be seen, wanting external validation, seeking to be the smartest person in the (online) room—and continues to deepen my understanding and repentance. Even with the Orthodox sphere online, perhaps because of it, I have seen how easy it is to mirror the world instead of transforming it.

It is incredibly difficult to unplug from the digital matrix and its influence on the ‘real world’ and this strange dichotomy seems as if it is following in the nominal footsteps of the West, divorcing symbol from reality; separating the sacred from the profane; God from the God-man, and by extension, God from man. Which leaves only man.

Fr. Alexander Schmemann critiques this performative religiosity, writing that this form of secular Christianity “[satisfies] a deep desire in man for a legalistic tradition that would fulfill is need for both the ‘sacred’—a divine sanction and guarantee—and the ‘profane,’ i.e., a natural and secular life protected, as it were, from the constant challenge and absolute demands of God. [The separation of the sacred and profane; the natural from the supernatural] was a relapse into that religion which assured, by means of orderly transactions with the ‘sacred,’ security and clean conscience in this life, as well as reasonable rights to the ‘other world,’ a religion which Christ denounced by every word of his teaching, and which ultimately crucified him.”[1]

This performative culture, where most things operate within a hyper-real world that seamlessly blends truth and fiction to create simulated experiences and piety, often overlooks God’s constant challenge and absolute demands. Every word of Christ’s teaching thus denounced this postmodern structuralism of reality. Jerusalem lies ahead, and the Lord foretells His disciples of His immanent crucifixion by the chief priests and scribes who have constructed a, as Fr. Schmemann calls it, grace-proof world, separating the natural from the supernatural and denying the world its natural sacramentality ultimately leading to secularism.[2]

The performative piety and purity tests found within the online discourse and apologetics the hyper-individualistic views of salvation and the self-proclaimed authority of the “Ortho-sphere,” the “Rad-trads,” and the Protestant fixation on “modern scholarship” produce not disciples of Christ, but isolated bishops, popes, and scholars using Christ to elevate themselves above others, the Church, and even Christ Himself. In a word, online spaces have become yet another grace-proof world.

This social fragmentation and isolation, devoid of grace, leads only to seeking after the praise and glory of men rather than the Truth found in Christ—that reality of who we are hidden with Him in God (cf. Col. 3:3). When we chase the praise of men, metrics, and engagement, we risk running counter to who we are, chasing the things of this fleeting world instead of what is eternal.

The Christian view of eternity lies in the Cross: That device of death being transformed into a symbol of life that we are called by Christ to orient toward, with Him, facing Jerusalem. He tells His disciples that salvation lies ahead, but with it comes persecutions (cf. Mk. 10:30). Thus, the Lord reminds us that following Him does not lead to mere elevation of status nor should one come looking for such honor by following Him (cf. Lk. 9:57-62).

This Sunday’s Gospel calls us back to the true cost of discipleship and while we can look at the sons of Zebedee and their request for material gain as something we’d never do if we were truly Christ’s disciples, yet we must ask ourselves: Are we truly Christ’s disciples or are we falling victim to the Pharisaical inclination to weaponize the law against our neighbor and to esteem ourselves as individuals set apart from others? The Lord gently calls His disciples, that means us, to the reality of what it means to follow Him, saying,

“You know that those who are considered rulers over the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones exercise authority over them. Yet it shall not be so among you; but whoever desires to become great among you shall be your servant. And whoever of you desires to be first shall be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give His life a ransom for many” (Mk. 10:42-45).

The Word of God reveals God to us: This revelation is not a passive monologue, but an invitation to communion, to participate in the life of Christ is to be united to Him, reflecting the self-giving love that God eternally exhibits for us all. Love is a gift from God, given to us all freely, out of His self-giving eternal mode of being, and to receive it is to experience what is True; experience the life of Christ and then give it to others. This is the call of Christians, and this is what it means to be witnesses.

The life of Christ is the Cross. This is the very life that Christ invites us into and to share. The life of service; putting off the old man and putting on Christ. St. Nikolaj Velimirović writes, “Whenever a person retreats… from this world and as often as he contemplates this world as existing without him and the deeper he immerses himself in reflecting about his unworthiness in this world, he will stand closer to God and will have deeper spiritual peace.”[3]

We live in a time where standing close to the world is more valuable than drawing near to God and in this time of Great Lent, as Jerusalem nears and the Crucifixion of our Lord awaits, we are called to pause and re-evaluate what insights we’ve gained in these past five weeks, and more importantly, what we’ve left behind.

Can we take some time this week to sit down and listen? Can we find time away from the screens and our desires to be seen by men to stand closer to God, in secret (cf. Matt. 6:6)? What is He asking us to let go of before we enter Jerusalem with Him? What is getting in the way of following, and uniting with, our Lord?

How can we slowly integrate our love for Christ into every day and every moment, rather than just on Sundays?

The Christian is called to participate in the world, sanctifying it with our presence, the very presence of Christ. This presence is not a show, nor is it a display of spiritual feats and fireworks. St. Paul, in his letter to the Thessalonians reminds us “that you also aspire to lead a quiet life, to mind your own business, and to work with your own hands, as we commanded you,that you may walk properly toward those who are outside, and that you may lack nothing” (I Thess. 4:11-12).

The Sunday of St. Mary of Egypt is not simply a commemoration of a fifth-century ascetic, but just such a call out of the world and toward God. St. Mary the Egyptian’s witness, prophetically, shows what is gained by forsaking all—dying completely to the self and crucifying the lusts of the flesh—for the Lord and the Gospel. She reminds us that though “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom. 3:23) it is never too late to begin anew and make a fresh start. No one is beyond redemption, and no one is too far gone to become radiant with divine love.

For as long as we draw breath, every moment we have is a gift of God to turn from the distractions and praise of men to stand closer to God. Every moment is an opportunity to renounce our self-sufficiency, autonomy, and worldly desires to become who we are in communion with Christ.

While the Lord promises persecutions for those who follow Him, yet He also promises eternal life, to abide in us as we abide in Him (cf. Jn. 6:56) “and the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding” (Phil. 4:7). The world cannot give us eternal life; neither metrics nor algorithms can offer peace that surpasses understanding.

Honestly, what the secular world leads us to forget is that Christ renders reality, not the algorithm and the more that embrace this technological matrix as the lens through which we perceive reality the less human we will become, the less we will see ourselves as made in the image of God, and the more the divide between God and man will become so the gap between man and machine decreases—we cannot serve God and Mammon, but the secular world claims the opposite.

So, what can we do?

How do we live out the Christian witness in this modern world?

There was a time that martyrdom meant dying for Christ—really dying—and though we live in a time that physically dying for our God seems radically easier than living the faith out, truly, in this secular world with its secular Christian trappings that suggests the times themselves are the persecutions. Christ promises them and they are subtle. We live in a world that blends truth and fiction, reality and narratives, a manufacture hyper-reality that offers comfort, convenience, and the praise of men. To be a martyr in this world is to go back to the original meaning of the word: Witness.

Where once we were called to give up our lives, now we are called to die in smaller, quieter ways: to die to our desire for applause (as someone who spent a decade doing stand-up this one is tough), to our constant need to be seen, and to our self-curated image. To be a Christian today means living the Gospel without comment, to carry our cross without performance, to be the very presence of Christ in the world, without a show, becoming invisible to the world, to become visible to God.

Christ is “the true light that which gives light to every man” (Jn. 1:9)—and His light is all we need.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ

[1] Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2018), 155.

[2] Ibid. 154.

[3] St. Nikolaj Velimirović, The Prologue of Ohrid: Lives of Saints, Hymns, Reflections and Homilies for Every Day of the Year (Ashok Vihar, Delhi: Facsimile Publisher, n.d.), 206.