Concerning presentism and Theosophy

“Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal; but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Matthew 6:19-20).

“For I want you to know what a great conflict have for you and those in Laodicea, and for as many as have not seen my face in the flesh, that their hearts may be encouraged, being knit together in love, and attaining to all riches of the full assurance of understanding, to the knowledge of the mystery of God, both of the Father and of Christ, in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge” (Colossians 2:1-3).

The free interpretation of the New Thought Movement is not a quirky feature of the tradition but highlights a larger cultural shift following the theories of higher criticism, which would shape the Bible—no longer a revelation of objective truth and reality to be lived like the early Christians—into a tool to be used for self-empowerment.

To quote New Thought writer, R.C. Douglass, “The clear province of the New Thought school of writers and teachers is not the abrogation of any Christian principles, but rather to give a better interpretation of those principles, consonant with truth, righteousness and health.”[1]

A better interpretation, through the lens of this spiritual science and its metaphysical pantheism would take on certain aspects that were similar to Christian Gnosticism, with the founder of Christian Science, a mind-cure movement practitioner, Mary Eddy Baker, declaring “All realm of the real is spiritual” and “Spirit is God, and man is the image and likeness; hence man is spiritual and not material.”[2] Additionally, New Thought author M. Douglas Fox, wrote in the article “The Great Power in and Trough All”,

“At the beginning of the nineteenth century the accepted ideas of God had become the opposite of those taught by Jesus the Christ, and they were to all intents and purposes those of the Jews of old. God was not a loving, tender Father; but a revengeful, capricious tyrant, who placed His newly created spirits in various bodies, and strongly contrasted environments.”[3]

I’m not saying biblical criticism leads to Gnostic heresy, but…

M. Douglas Fox and Mary Eddy Baker are putting forth ancient heresies of the Christian Church, in rejecting the material world one is declaring that it is either evil or does not exist; by declaring the God of the Old Testament a capricious tyrant one is falling into the Marcionite heresy of rejecting this God for a different one, teaching “its first vital fundamental, the one mind in all and through all.”[4] A clear demonstration of the mind-cure movement’s roots in the pseudo-Hermetic Principles, namely: All is Mind, the Universe is Mental.

While the Gnostic elements were not so widespread at the time, the mind-cure movement was vastly popular during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was primarily due to the fragmentation of societal solidarity. The influence of the Enlightenment’s rationalism, intellectualism, and Romanticist individualism were catalyzing agents for eisegeitcal interpretations to be taken up with such vigor.

During the height of its popularity, New Thought drew criticism for its thin veil of esoteric wisdom, covering its core motivation for profit. The American historian Alfred Griswold observed the movement’s teachings based on self-willed prosperity, a virtue he related to the Puritans as much as it was certainly a virtue in turn of the century America. He referred to adherents not being particularly adept at its metaphysics or theology past the promise and philosophy of success, which accorded to traditional American values. His evaluation of the movement’s literature concluded in the summation that “the literature contains little but esoteric directions for making money.”[5]

Despite the criticism, New Thought’s broader cultural appeal led to a greater number of people seeing Scripture as a tool using its contents to justify self-oriented financial gain, slowly shedding the need for a Messianic Savior figure at all. Highly influential, New Thought’s current still resonates in the larger culture, with its self-help, self-improvement, and literature focused on positive thinking it.

This esoteric direction shaped the spiritual landscape placing emphasis on the inner world of the individual and their role as the arbiter of authority. These ideas would be refashioned in the West through the New Age movements, the Prosperity Gospel, and the spiritualized, commodified self-help genre.

The New Thought Movement’s broader cultural impact demonstrates further mainstream departure from early Christianity’s orthodox presuppositions and exegetical realism. This theological orientation provided societal structure by its communal solidarity and correspondence in history, grounding the community in sequential history moving forward together—united in Christ—toward a shared eschatological fulfillment.

The common telos interwoven in the actions of the Messiah in time and the eternal work done through the Cross, reconciling all people everywhere to Him, echoed by the Apostle, that “there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28).

When Christ’s teachings are extracted to support one’s own ambition and material wealth then this societal union fragments and dividing lines emerge. This detracts from the universal message of redemption of human nature in Christ and the inherent dignity of all, reducing the Gospel message to an individualized good. A good that has been rendered, therefore, subjective. It can be argued that this approach is a consequence of Semler’s hermeneutical lens, separating dogmatic theology from historical context.

Jesus’ call to care for the poor is thus an element of his earthly, historical ministry, however His hidden mind-cure teachings were of divine substance. Shifting the focus away from the needy toward New Thought practitioner’s desires. The exegetical lens would undermine the rational egoism of New Thought and the larger nexus of American individualism. This eisegetical schema subtly hints that society, once united, has now moved beyond this outdated form of thinking, enlightened by esoteric thought and egoism.

For, indeed, if Jesus is taken at His word and we understand Him to be saying what He means and meaning what He says, then one might need to contend with the idea that the esoteric directions for making money are but the very methods that one serve Mammon. However, if Jesus’ teachings are, in fact, pointing toward an occultic message then neither of His early followers, ministers, or His Church need be heard, either. When St. Basil laments over the rich and their treatment of the poor such as in the third century homily,

“For whoever has the ability to remedy the suffering of others, but chooses rather to withhold aid out of selfish motives, may properly be judged the equivalent of a murderer.”[6]

The innovative interpretation would be to suggest that the dogmatism of the saint’s message must, too, be separated from its historical context.

Gotthold Lessing’s critical lens provided a foundation for separation while also contributing to the later esoteric schools’ reinterpretation using their own form of theological presentism. This was not merely seeking to understand dogma divorced from historical context, but by blending elements of Lessing’s higher criticism and the groundbreaking Life of Jesus Critically Examined by Strauss, the burgeoning mystery schools would reinterpret Scripture, and the Christ figure. These schools would contrast the financial-focus of the New Thought Movement, using their own mystical language, symbolism, and eclectic philosophies and religious frameworks they sought to liberate mankind from the material world.

Theosophy emerged as an intellectual and mystical counterpoint to New Thought in the late nineteenth century. While sharing a focus on individual spiritual elevation, Theosophy eschewed materialism, seeking instead to synthesize Eastern and Western philosophies to transcend the physical world. H.P. Blavatsky, a mystic and author, with her deep study of Eastern lore developed “philosophical-religious system which claims absolute knowledge of the existence and nature of the deity” and this knowledge “may be obtained by special individual revelation.”[7]

Though New Thought centered on material prosperity, Theosophy’s aspirations were more explicitly mystical, aiming at the spiritual liberation of humanity through an esoteric framework. Yet, both movements contributed to the broader cultural shift from the communal salvation offered in Christian orthodoxy to highly individualized spiritual paradigms.

The Theosophical Society played a significant role in the West, not only presenting the exotic Orient which was certainly more appealing than the deracinated Christianity of the post-Enlightenment age but would also contribute to the overwhelming changing trend “to emphasize the association of ‘spirituality’ with the interior life of the individual.”[8]

The emphasis on the interior life of the individual marked further departure from the early communal nature of religious paradigms, both Christian and not. The Theosophical Society viewed their aims in relation to the astral plane, teaching that it is humanity’s duty to ascend the states of consciousness, thereby uniting with the divine, often called the Absolute in Theosophy and other Neoplatonic schools.

This spiritual current therefore made use of Scripture, both biblical and extra-biblical to support its claims that the purpose of humanity is to raise their consciousness toward the divine. The teachings of Jesus Christ would, again, be used to further the agendas of an esoteric few, claiming that they held the keys to true religion.

The Theosophical Society treated Jesus similarly as the New Thought Movement in that He was an Ascended Master—a normal human being that had attained spiritual adept-hood akin to the Buddhist bodhisattva. Christ was a teacher, an initiator of the individual into the divine mysteries, separated from dogmatic theology, that would enable the initiate to begin the process of self-realization and be liberated from Samsara, or the cycle of death and rebirth.

In Theosophy, Christ was reduced to a principle of divine wisdom, influenced by Strauss’ Life of Jesus. This interpretation detached Christ from theological dogma, recasting Him as a mythological figure and a personal archetype latent within every individual, aligning with Blavatsky’s esoteric vision.[9] The Christos, as it is called in Theosophy, is an archetype of self-transformation. This self-transformation aimed at the elevation of consciousness toward union with the divine, presented through an imaginative lens of applied presentism and syncretic spirituality.

The grand cosmic plan of Theosophy is this self-transformative work that humanity is called to, to raise one’s consciousness, individuate, and become one with the Absolute. Two things this demonstrates is 1) the larger cultural shift toward individualized spirituality, commodified and offered by eisegetical interpretations filtered through personal agendas and eclectic religiosity. And 2) a profound reduction of the cosmological scale of Christ’s redemptive work on the Cross; Theosophy is, quite intentionally, presenting a gnostic gospel of a Christos principle rather than the reality of the Incarnation, Who we believe and confess to be “the beginning and cause of all things.”

St. Maximus the Confessor, a seventh century monk and champion of the faith writes in contrast to this Neoplatonic, self-oriented system of pantheistic self-transformation, talking of Christ’s cosmic resonance, he continues:

“This same Logos, whose goodness is revealed and multiplied in all things that have their origin in him, with the degree of beaty appropriate to each being, recapitulates all things in himself (Eph. 1:10). Through this Logos there came to be both being and continuing to be… and by continuing to be and by moving, they participate in God.”[10]

This participation is predicated on our relationships with one another, reflecting the nature of the Trinity.

Jesus Christ, the Christ within as the New Thought writers called it, or Christos as the Theosophical Society refers to it, becomes a personal, individual archetype, reducing Him to a principle of wisdom, further reflecting the post-Enlightenment cultural shift toward the elevation of the intellect and rationalism. Christ is all in all; the Trinity is the eschatological fulfillment, revealed by the messianic presence in time to a community.

As we all have our origins in the One, the one is many, and we are united in the One—that is the Triune God, not an abstract Absolute. The Logos “is the substance of virtue in each person,”[11] underscoring our call to act within time and community, to do well, to allow the grace of God to work within us and transform us moving from glory to glory (2 Cor. 3:18).

The transformative work of God exudes out, like the sun’s warmth, and His glory is revealed in and through the virtues which is grounded in Christ. The ground of all goodness is in Christ.

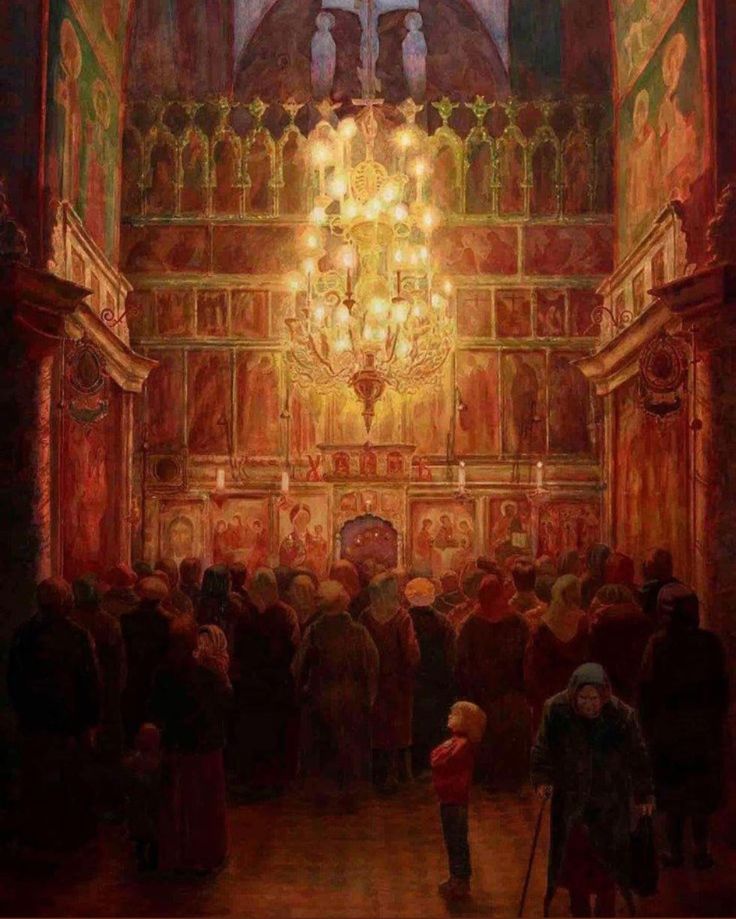

This is the cosmic plan, to reconcile all of Creation to God through Christ. We participate in that by participating in the divine life in community, the Body of Christ in His Church. He is the head of the Church as the Messiah of His people, and He recognizes His own and His own recognize Him (Jn. 10), wherein we become more and more likened to Him in our communal solidarity.

Ο ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΕΝ ΤΩ ΜΕΣΩ ΗΜΩΝ! ΚΑΙ ΗΝ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΣΤΑΙ

[1] Dresser, History of the New Thought Movement, 52.

[2] Ibid. 38.

[3] Ibid. 80.

[4] Ibid. 81.

[5] Alfred Whitney Griswold, “New Thought: A Cult of Success,” American Journal of Sociology 40, no. 3 (1934): 309–18, accessed November 19, 2024, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2768263.

[6] St. Basil the Great, On Social Justice, trans. C. Paul Schroeder (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2009), 85.

[7] Leslie Shepard, Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, vol. 2 (Detroit, MI: Gale Research Company, 1984), 1353.

[8] Carrette and King, Selling Spirituality, 41.

[9] “Jesus Christ,” Theosophy World Encyclopedia, accessed November 18, 2024, https://www.theosophy.world/encyclopedia/jesus-christ.

[10] St. Maximus the Confessor, On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ, trans. Paul M. Bowers and Robert Louis Wilken (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 55.

[11] Ibid. 58.