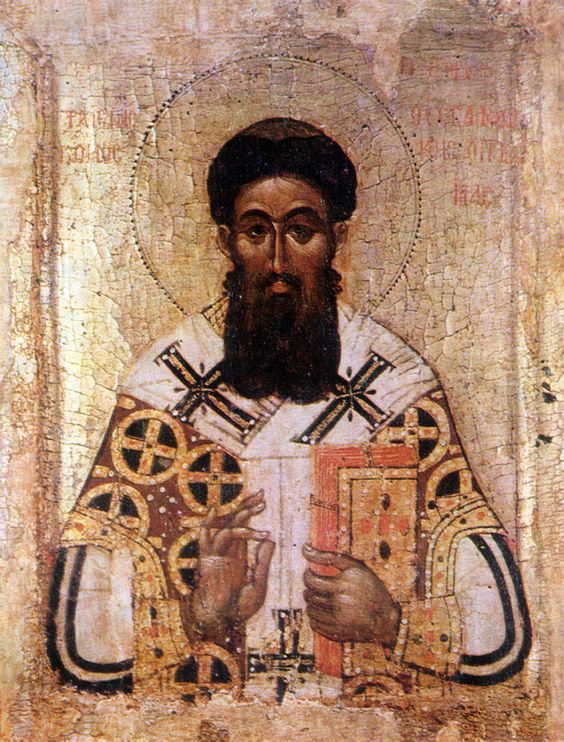

The Sunday of St. Gregory Palamas

“When he returned to Capernaum after some days, it was reported that he was at home. So many gathered around that there was no longer room for them, not even in front of the door, and he was speaking the word to them. Then some people came, bringing to him a paralyzed man, carried by four of them. And when they could not bring him to Jesus because of the crowd, they removed the roof above him, and after having dug through it, they let down the mat on which the paralytic lay.

When Jesus saw their faith, he said to the paralytic, ‘Child, your sins are forgiven.’ Now some of the scribes were sitting there questioning in their hearts, ‘Why does this fellow speak in this way? It is blasphemy! Who can forgive sins but God alone?’ At once Jesus perceived in his spirit that they were discussing these questions among themselves, and he said to them, ‘Why do you raise such questions in your hearts? Which is easier: to say to the paralytic, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’ or to say, ‘Stand up and take your mat and walk’? But so that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sins’—he said to the paralytic—‘I say to you, stand up, take your mat, and go to your home.’

And he stood up and immediately took the mat and went out before all of them, so that they were all amazed and glorified God, saying, ‘We have never seen anything like this!” (The Gospel According to St. Mark 2:1-12).

This Second Sunday of Great Lent in the Orthodox Church is known as the Sunday of St. Gregory Palamas, in a continuation of last week’s Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy we have come to this next step into the desert with Christ. There is much to be said about this day and why St. Gregory Palamas is commemorated today, but in a few words, we can boil it down to this: St. Gregory’s victory in the hesychast controversy of the 14th century is no victory for a single man, but an entire Church.

That victory is the recognition of God’s love and the salvation found in Him.

Hesychasm is a practice that has been held to since, at least, the 3rd and 4th centuries being refined and developed by the Desert Fathers and Mothers that eventually became a traditional practice on the Greek isle of Mount Athos. It means stillness and it is through which we as individuals develop an interior life of prayer with the aim of encountering God, becoming united to Him by His grace.

This grace, what is also called God’s uncreated energies, is what this contemplative practice moves the practitioner into participating in and thereby participating in God’s divine life (2 Peter 1:4). St. Gregory took great pains and entrenched himself in Scripture and the writings of the Patristics to outline the distinction between God’s essence, which is by its nature, incomprehensible and unknowable to created beings. However, God’s energies are the dynamic manifestations of His unknowable essence. These energies are the method in which God interacts and reveals Himself in Creation.

These energies are what we, as Christians, seek to encounter and participate in, becoming more and more like God through this participation in His energies by grace. The encounter with His energies, concretely understood as occurring during Divine Liturgy can also manifest themselves as is what has been known as the “light of Tabor” or the “uncreated light”, which practitioners of the hesychast tradition have reported since its emergence in the desert.

Before going on, it is important to note that while this is a mystical experience of encountering the uncreated light (which practitioners do not have to witness to participate in), the observation and its effects have been consistently reported by those practicing it. It is a well-documented, empirical, epistemological framework.

Now, what we must understand is that the hesychast controversy with St. Gregory Palamas on one hand and the heretic Barlaam on the other was a debate about theological schema as much as it was about philosophical concepts. Barlaam of Calabria argued in favor of intellect and reason being the primary source for the acquisition of truth and knowledge. For context, this is a continuation of the scholasticism that developed during the Medieval period in Europe; a development that had not affected the East in the same way.

St. Gregory showed this in his treatise defending hesychasm stating that God is not a philosophical concept as He becomes through the lens of rationalism and materialism, but rather God is love (1 John 4:7-8). And God has revealed Himself to us a Living Person Who is a consuming fire (Deuteronomy 4:24; Hebrews 12:29), proving us and making us like Him by His grace. Through the mystery of baptism, we enter into the Body of Christ, again this is not a philosophical concept, but a real, living entity in which the indwelling Holy Spirit sanctifies our minds and bodies through the Sacraments, the zenith of which being the Eucharist.

It is through this tradition of hesychasm, ascesis and contemplative prayer, that the indwelling grace of the Holy Spirit is cultivated. The Spirit of God thus cleanses the faculties of the mind, what we would call the nous—the intellect of the heart—and slowly purifies this looking glass, uniting us more and more to God via the uprooting of the passions. This practice is of the mystical empiricism school in which our epistemology is based on realism and experience.

This epistemological framework does not deny the transcendent nature of God’s essence, that which is unknowable, unfathomable, and unperceivable; “No one has ever seen God. It is the only Son, himself God, who is close to the Father’s heart, who has made him known” (John 1:18). The glory of God, participable in His uncreated energies, or light, are encountered through our becoming like the Son, Who made His Father known on Mount Tabor during the Transfiguration.

The central argument of St. Gregory’s treatment of the energies and essence of God is that we are able to be deified through participating in God’s uncreated glory. It is not a full rejection of Barlaam’s position of scholastic rationalism. St. Gregory fuses both mystical empiricism with the recognition that we as created beings cannot grasp at the unknowable, transcendental essence of God. We can know Him through participating in His uncreated energies, however, developing a practical epistemology in regard to the nature of God and man’s place in Providence.

What we can infer from this intersection is that we are known to ourselves as we know God, without effort we can know neither God nor ourselves. St. Gregory’s theology provides the groundwork for Orthodox thought and praxis in regard to man’s relationship with God and our fellow man.

What our baptism into Christ reveals is that our own nature is just as unfathomable as God’s essence due to it being made in His image, and because like recognizes like the more we draw closer to God, revealing Him through ascetical and contemplative effort the more we draw nearer to ourselves, who can only be realized in Christ.

We believe, based on the records kept since the Patristic age, that we men can participate in the divine life, becoming divine, becoming like God by His grace in the Holy Spirit. We have access to this ability through being members of His Holy Church, grafted into the Body of Christ thereby experiencing His energies through Liturgy, the Sacraments, and hesychasm itself.

Why this is so invaluable to someone like me, raised in the Aristotelian West of category, memorization, and hyper-intellectualism deeply ingrained in a material objectivist society, is because I am liable to become so trapped in my own head that the only way out is to develop idols. The essence of God need become concrete for me to grasp it, lest I drift away…

Personally, I think that this is one of the shortcomings of the Western tradition of scholasticism and what becomes painfully obvious to one who swims the Bosporus is that the prioritization of reason, logic, and intellect is a deeply flawed epistemological system to understand God’s love.

There are so many books, theological treatises, chants, prayers, saints, the lives of saints, metaphysics, etc. etc. Orthodoxy, when approached from the mindset of trying to “figure it out” and intellectually grasp it is like using rationalism to understand the transcendent essence of God. Sooner or later, it will feel as if we are drowning, the pressure of the spiritual path, fighting the weight of the immense body of theological water, losing strength and being carried away by the current, lost at sea.

This is a problem in many spiritual traditions where one becomes so engrossed in the material they lose sight of the forest for the trees; the waves crash against us under the dark skies until we have no idea which way is up.

St. Gregory’s victory is not a disavowal of the intellectual tradition of the Church, nor is it a rejection of philosophy. The victory lies in being able to let go of the faculties of the mind to unite with God by His grace. We commemorate God’s love for man, the love that deifies His Creation, making us more like Him through a synergistic relationship of ascesis, contemplation and God’s grace. If we look at the Gospel reading, the paralytic tirelessly works to gain access to Jesus and He is healed by faith.

This is the grace St. Gregory Palamas’ theology outlines; this sort of relationship, becoming united to God by participating in His uncreated energies costs. While God’s love is freely given to all through baptism we are entering into a different kind of relationship with Him, one in which we are responsible for cultivating the indwelling Holy Spirit to become living persons ourselves by His deifying, consuming fire.

Barlaam’s arguments implicitly usher in a new era of religious apathy and ascetical indifference. If God is a philosophical concept then so is His love, to which we become so far removed from His Living Love and Presence that Christ’s sacrifice nullifies any struggle on our side. It must cost us something to seek divinity. Considering that the Orthodox view salvation in terms of theosis, it cannot possibly cost us nothing.

To quote Bonhoeffer, “Cheap grace is not the kind of forgiveness of sin which frees us from the toils of sin. Cheap grace is the grace we bestow on ourselves. Cheap grace is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, Communion without confession, absolution without personal confession.

Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate.

Costly grace is the treasure hidden in the field; for the sake of it a man will gladly go and sell all that he has. It is the pearl of great price to buy which the merchant will sell all his goods. It is the kingly rule of Christ, for whose sake a man will pluck out the eye which causes him to stumble, it is the call of Jesus Christ at which the disciple leaves his nets and follows him.

Costly grace is the gospel which must be sought again and again, the gift which must the asked for, the door at which a man must knock.

Such grace is costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ. It is costly because it costs a man his life, and it is grace because it gives a man the only true life.”

Barlaam’s philosophy is this same sort of cheap grace that neatly defines God as a totally unknowable, transcendent idea. This is halfway to idolatry, though, because if that is the case then who is stopping anyone from projecting qualities onto the unknowable God? No, this is blasphemous in the case of a True, Loving God Who seeks and wills for all men to be saved (1 Timothy 2:4), but He is not a tyrant, for He is love, so man must enter into relationship willingly with Him to become like Him. If it were any other way this would not be love, it would be coercion. God does not coerce; He unites man to Himself out of love.

And we do not enter into that sort of relationship with ourselves, cleansing the glass of the nous and becoming aware of ourselves: of who we really are in Christ and how our passions move us away from being healed by our God. This is kind of awareness is not cheaply gained, either. The life of a Christian is a life wrestling against the temptations, fighting the dragons of our souls, and being perfected by Christ, refining the indwelling of the Spirit within us.

This is love. This is God, this is God’s essence right here: to want us to be perfect, to be united with Him. Philosophical concepts do not function in the same way. Barlaam’s scholasticism and proto-humanism would go on to inspire to Italian Renaissance and from there play a role in the Enlightenment, eventually leading to erosion of the Western Church via Human Idealisms’ influence on the Protestant Reformation. This can be seen in the (particularly) American Christian tendency toward demystification and inherent rationalism doctrinally combating the very purpose of the Incarnation, which is to deify Creation out of and by God’s love for us.

The triumph of Orthodoxy commemorated on this second Sunday of Lent honoring St. Gregory Palamas’ theological groundwork that oriented the Orthodox Church truly looking to God and His love in all things. It is a loving God that wants us to be like Him; there are no gods that seek the same. The fully realized man can be actualized through ascetical and contemplative practice, strengthened by the sacraments, and grafted in unity to God, the Living Person, through the mystical Body of Christ.

It is only through the Church that this inherent potentiality can be realized in Christ. And to believe that means to do whatever it takes to encounter His energies, like the paralytic from today’s Gospel reading, no matter what we do ascetically or contemplatively the aim is to participate in His healing and uncreated energies, to burn away the passions and revealing His likeness within us and ultimately to be utterly transformed and united to Him. For our God is a consuming fire. Selah.

“O Gregory the Miracle Worker, light of Orthodoxy, support and teacher of the Church, comeliness of Monastics, invincible defender of theologians, the pride of Thessalonica, and preacher of grace, intercede forever that our souls may be saved” (Apolytikion).

Si comprehendis, non est Deus