The Sunday of the Passion

“As soon as it was morning, the chief priests held a consultation with the elders and scribes and the whole council. They bound Jesus, led him away, and handed him over to Pilate. Pilate asked him, ‘Are you the King of the Jews?’ He answered him, ‘You say so.’ Then the chief priests accused him of many things. Pilate asked him again, ‘Have you no answer? See how many charges they bring against you.’ But Jesus made no further reply, so that Pilate was amazed.

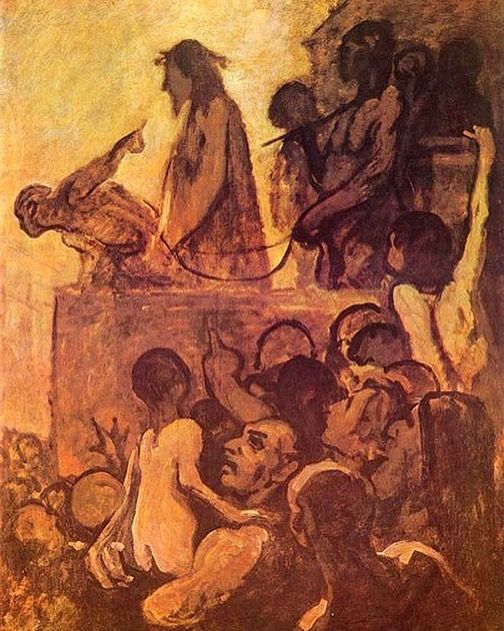

Now at the festival he used to release a prisoner for them, anyone for whom they asked. Now a man called Barabbas was in prison with the insurrectionists who had committed murder during the insurrection. So the crowd came and began to ask Pilate to do for them according to his custom. Then he answered them, ‘Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews?’ For he realized that it was out of jealousy that the chief priests had handed him over. But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to have him release Barabbas for them instead. Pilate spoke to them again, ‘Then what do you wish me to do with the man you call the King of the Jews?’ They shouted back, ‘Crucify him!’ Pilate asked them, ‘Why, what evil has he done?’ But they shouted all the more, ‘Crucify him!’ So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released Barabbas for them, and after flogging Jesus he handed him over to be crucified.

Then the soldiers led him into the courtyard of the palace (that is, the governor’s headquarters), and they called together the whole cohort. And they clothed him in a purple cloak, and after twisting some thorns into a crown they put it on him. And they began saluting him, ‘Hail, King of the Jews!’ They struck his head with a reed, spat upon him, and knelt down in homage to him. After mocking him, they stripped him of the purple cloak and put his own clothes on him. Then they led him out to crucify him.

They compelled a passer-by, who was coming in from the country, to carry his cross; it was Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus. Then they brought Jesus to the place called Golgotha (which means Place of a Skull). And they offered him wine mixed with myrrh, but he did not take it. And they crucified him and divided his clothes among them, casting lots to decide what each should take.

It was nine o’clock in the morning when they crucified him. The inscription of the charge against him read, ‘The King of the Jews.’ And with him they crucified two rebels, one on his right and one on his left. Those who passed by derided[e] him, shaking their heads and saying, ‘Aha! You who would destroy the temple and build it in three days, save yourself, and come down from the cross!’ In the same way the chief priests, along with the scribes, were also mocking him among themselves and saying, ‘He saved others; he cannot save himself. Let the Messiah, the King of Israel, come down from the cross now, so that we may see and believe.’ Those who were crucified with him also taunted him.

When it was noon, darkness came over the whole land[g] until three in the afternoon. At three o’clock Jesus cried out with a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?’ which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ When some of the bystanders heard it, they said, ‘Listen, he is calling for Elijah.’ And someone ran, filled a sponge with sour wine, put it on a stick, and gave it to him to drink, saying, ‘Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to take him down.’ Then Jesus gave a loud cry and breathed his last. And the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. Now when the centurion who stood facing him saw that in this way he breathed his last, he said, ‘Truly this man was God’s Son!’” (The Gospel According to St. Mark 15:1-39)

Following Jesus into the Passion narrative found in the Western churches this week must begin with the knowledge that Jesus is the pre-eternal Word, the second hypostasis of the Trinity, and God Himself. The West typically, and with almost reckless credal-abandonment in the far West, focuses on the humanity of Jesus Christ far more than His Divine nature. This is, of course, to be expected because it really is the humanity of Jesus that one can readily relate to.

He is a figure of wisdom, a master of prayer and contemplation, and a exemplar of godly, longsuffering patience. The Passion invites us to witness this man we call Jesus endure betrayal after betrayal, beating after scourging, insult, injury, and finally death in a humiliating fashion on a cross. He died amidst transgressors, being assaulted by unbelievers and mockers, given up to the jealous religious leaders of His time who wanted nothing more than to be rid of Him to re-establish their leadership and power.

It is easy to see this narrative as simply a spiritual leader and revolutionary executed at the height of His fame by the powers that be to keep Him quiet and those with Him in line. It is easy, because this keeps Jesus somewhat tame and sanitized. This keeps Him at a safe distance where He becomes this sort of figurehead of a revolution in this period of Second Temple Judaism. But see, this is us, now, still choosing Barabbas when given the choice by Pilate. It is much easier to choose Barabbas and even follow him!

We project onto the humanity of this revolutionary figure with our present-day problems and politicking; in our focus on the humanity of the eternal Word we are, inadvertently, freeing Barabbas and putting to death Jesus Christ. I can understand this, I’m like everyone else, lips proclaiming Christ, but heart choosing Barabbas’ rebellion. The Passion narrative does many things, it tells us Who Jesus is and it tells us who we are in relation to Jesus. When we focus too heavily on His humanity, we enter into a heretical line of thinking wherein we relate Jesus to ourselves rather than the other way around.

If Jesus died for us then why, oh why, would we try relating Him to us?

No, the point of the Passion is to enter into contemplating the Mystery of Jesus Christ and how we relate to Him. He Himself has related to us, for He condescended and took flesh to be amongst us; this was not done so that we would find a way to apply Jesus to our lives, but so we could apply ourselves to the life of Christ.

How might we choose Barabbas in our lives?

I wonder how many of us do so without even thinking, ascribing certain qualities of character that we, individually, idealize onto Jesus. Unless we idealize the qualities of Jesus Christ then we are only projecting onto a figure and then projecting this figure onto Scripture and others. With that said, it might be good to spend this Holy Week looking at just exactly why Jesus died on the Cross in the first place.

This being the Western tradition’s time of the Passion it seems only right to begin by looking at the propitiatory theory of atonement: which states that Jesus died as a substitution for us. The punishment of sin is death, so Jesus’ death is in place for all. This theory carries a Reformed connotation a lot of the time where Jesus is pitted against God the Father, as suffering the wrath of God meant for humanity because of our disobedience as well as even losing His Divinity through His death before having it restored through His resurrection! The other, similar, atonement theory is the satisfaction theory that is taught in Roman Catholicsm and, via this channel, made its way into less Reformed Protestant traditions: this theory states that Jesus’ death satisfies the justice of God where sin is an injustice and through Jesus’ death balance returns because He paid humanity’s debt owed to God.

In both cases, there is a debt owed to God and a metaphysical judiciary system at work in which we are all declared not guilty by the sacrifice of Christ. These models, however, keep us entrenched in the courtroom where we, by putting Jesus to the Cross, declare Barabbas not guilty and by extension our own continued rebellion. So, let’s instead take a recess, step outside and look at Creation with a new lens.

Through the very lens of the Resurrection.

Death, the punishment for sin, is not a natural part of the human life. Death is a consequence of our fallen nature. Man was not made for death, but through man’s disobedience to God death entered the world. Death is a merciful end for us, or we would be crystallized in this fallen form unto the ages of ages, yet God in His compassion allowed us to die.

What must be stated, here, is that God is not the architect of death, but it is the deceiver and man willingly entered into this mortal state by his rebellion against God. We entered into death by doing as the fallen angels had done, the very one we find on the tree who offers man the chance to become like God without God. In this way, man followed the fallen angels in their rebellion and descent, becoming rather children of the devil, “The children of God and the children of the devil are revealed in this way: all who do not do what is right are not from God, nor are those who do not love a brother or sister” (1 John 3:10).

Being a child of the devil does not mean we are begotten by Satan, but rather that we are imaged into his likeness by committing sin, “Everyone who commits sin is of the devil, for the devil has been sinning from the beginning. The Son of God was revealed for this purpose: to destroy the works of the devil” (1 John 3:8). And here we see an indication of why the Word of God, the second hypostasis of the Trinity, condescended and took flesh: to destroy the works of the devil.

To destroy death.

The devil has been sinning, has been working in man, from the beginning. So, to see the scope of the Passion we must go to the very beginning. And to do that, we need to acquaint ourselves with the imagery of the Holy Mountain, which place the ancient Hebrews went to draw near to God. This mountain is found throughout Scripture: The Prophet Moses speaking to God on Sinai and Horeb; where Abraham ventures to offer Isaac to God; Mount Hermon, Mount Tabor, and the Sermon on the Mount, you get the idea.

The Mountain of God is known by many different geographical names but is all of them God’s Holy Mountain. This is where we, too, like the ancient Israelites draw near to God, seen in the Transfiguration in the New Testament; this is the place where Heaven and earth meet, (meta)physically. Something we often miss, however, is that the heavens and the earth were married on a mountain in the very beginning.

We will look turn our eyes to the first Holy Mountain, First Man, and how all that ties into the Passion of the Son of God in tomorrow.

Si comprehendis, non est Deus