The First Sunday of Lent

“In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove upon him. And a voice came from the heavens, ‘You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.’

And the Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness. He was in the wilderness forty days, tested by Satan, and he was with the wild beasts, and the angels waited on him.”

Now after John was arrested, Jesus came to Galilee proclaiming the good news of God and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news’” (Mark 1:9-15).

Yesterday was the First Sunday of Great Lent, marking the beginning of our Lenten sacrifice wherein we enter a time of reflection, repentance, and contemplating the Mysteries of the Passion. The Gospel reading shows us a newly baptized Christ being led into the wilderness to be tempted by Satan.

Here we have the foundation for Christian monasticism with the early Christians being led by the Spirit into the deserts outside Roman Egypt in the early centuries. There, they did battle with demons and the tempter, Satan. The tradition was that the demons lived in the desert and these early monks were intentionally going to live amongst them, bringing Christ into enemy-occupied territory to shine a light on the dark, desolation of the desert. I am invigorated thinking about our brave fathers and mothers who abandoned the world to carry Christ into the dark.

This so embodies the footsteps of Jesus Himself stepping out into the wilderness, to be tested, and to be with the wild beasts. Before Jesus walked along the coastline of Galilee, calling the fishermen from their boats to follow Him, He was with the wild beasts. We know the sort of temptations that Satan offers Jesus, and I was tempted, myself, to write about turning away from the world to follow Christ; flee from what the devil offers. But then, of course, we know to flee from the temptations of Satan, whether or not we indeed flee from them is a different story, of course. We know the temptations, but what are these wild beasts doing here?

The wild beasts in Greek is θηρίον, or therion, which means—wild beasts, who would’ve thought, but in addition to the literal meaning it metaphorically means “wild and brutish; a beastial man.”

Now, I am not trying to illustrate a Jesus of Nazareth walking into a desert full of people eating crickets and honey, covered with camel hair. No, He had just been baptized by that sort of man.

However, this points to an interesting relationship between the Gospel and the reading from Genesis:

“Then God said to Noah and to his sons with him, ‘As for me, I am establishing my covenant with you and your descendants after you and with every living creature that is with you, the birds, the domestic animals, and every animal of the earth with you, as many as came out of the ark. I establish my covenant with you, that never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of a flood, and never again shall there be a flood to destroy the earth.’ God said, ‘This is the sign of the covenant that I make between me and you and every living creature that is with you, for all future generations: I have set my bow in the clouds, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth. When I bring clouds over the earth and the bow is seen in the clouds, I will remember my covenant that is between me and you and every living creature of all flesh, and the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh. When the bow is in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is on the earth.’ God said to Noah, ‘This is the sign of the covenant that I have established between me and all flesh that is on the earth’” (Genesis 9:8-17).

The Noahide covenant, made between Noah and God, covered all Creation; it included every living creature, as many as came out of the ark with Noah. This covenant promised that God would never again cut off flesh by the waters of the flood or flood the earth to destroy it. He set a bow in the clouds to be the sign of the covenant between Him and the earth.

The promise that the waters shall never again become a flood to destroy all flesh. All flesh. It might be a little unorthodox to say having grown up with the understanding that Noah is our ancestor, but for a moment, I wonder how we might view ourselves considering the animals that came out of the ark our ancestors.

These birds, these domesticated, and these… wild beasts emerging from the flood waters unscathed because of the shepherd Noah. The promise of this Covenant was established before the waters covered the earth, the covenant was being established by the building of the Ark. This, most obedient soul, Noah listening to God and carefully taking our ancestors into His Temple.

The promise of this Covenant are fulfilled in Jesus’ baptism at the Jordan, directly before His being led into the wilderness; the ascension of the bow of God’s covenant and the descent of the Holy Spirit, as a dove, unifying in the Godman Christ, imbuing the waters of this earth with eternal life. Now, it was not simply a promise that the waters would never again destroy the earth, but now the waters could save Mankind, the waters would never again cut off the flesh from God, but bring the flesh into the salvific nature of Christ.

It is not a sign, an ordinance, or just an external expression of an internal process: this is becoming one with God by following the footsteps of Christ, wet as they were. We see this in the Epistle reading, in the words of St. Peter:

“For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight lives, were saved through water. And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you—not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers made subject to him” (1 Peter 3:18-22).

I don’t mean to offend anyone who might take offense, but really consider this idea that, our ancestors walked onto and off the ark, two by two, because in the former days there were only eight lives who were saved through water. They went for forty days into the dark, desolate water. And they were there with the wild beasts.

The Anglican Communion has, as its own ancestors, the Celtic monks who established the Anglican tradition of Catholicism in the British Isles in the third and fourth centuries, to which we trace our roots back. In the Eastern tradition of Christianity Mt. Athos, in Greece, is thought to be the container of true, Orthodox spirituality and monasticism. The same might be said about the abbey of Iona in Scotland.

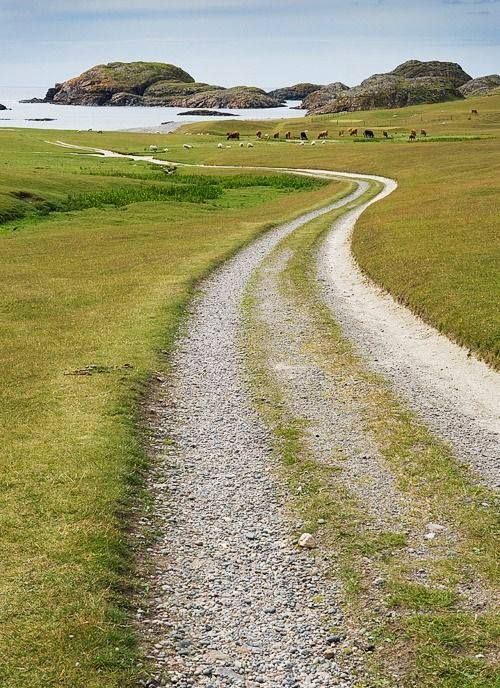

Though this island off the Western Coast of Scotland is surrounded by seas, forests, rivers, and crooked rock formations here the Celtic monks found their desert. The word comes up quite a bit in their writings, where they saw the sea as the desert, the still waters holding nothing in eyesight into the void of the horizon, at any moment turning to storms, rocks, jettisoning ships at any moments, and, of course, the wild beasts that lie below the surface.

What lies beneath the surface of our desert, I wonder. What lies beneath the surface of our waters? In the Gospel narrative, Christ comes to be with the wild beasts, no doubt taming them in much the same that we see monastics throughout history taming wild beasts like St. Seraphim of Sarov, but I wonder if we could recognize ourselves as those wild beasts, taking a note from our early Celtic forefathers and, using Scripture, seeing them metaphorically.

The two covenants are unified in Christ, covering us through our own baptisms where we see that God would never again destroy the creatures of this earth; instead, He uses those same waters to energize our beastial nature by the Spirit and therefore allow us to be continuously energized by the Spirit and, ultimately, divinized. Christianity is not bathing the man and giving him a haircut, but through baptism we are appealing to God for a good conscience. This conscience, taken from the Greek, συνείδησις (suneidésis), means joint-knowing properly, the commingling of moral and spiritual consciousness which is a product of our being made in the divine image.

Jesus Christ is the light of the world, He is the conscience becoming aware of itself, without Him the conscious mind would still live in darkness, still live under the shroud of Satan, still live as a wild beast.

Still living disobedient to God, in original sin: unrighteous, unworthy… brutish.

But see, this is the power of the Gospel—the good news—that God loved us despite our fallen nature and did everything to ensure we could be made whole, again–unified with Him through His Son Jesus Christ. Who is the joint-knowing of heaven and of earth. He is the joint-knowing of the covenants, unifying the Spirit with the promise. Through the waters of baptism, we become one with the Spirit and the promise. We enter into joint-knowing both Christ and who we are by the Spirit, and with Christ and through Christ we enter into the Christian process of transformation known as theosis, becoming more and more like God by His grace.

This process will be uncomfortable and will ask a lot out of us, it will ask us to step into an awareness of self that is so foreign it is like stepping into the deserts of Egypt or into the a gnarled Scotland.

We follow Christ into the wilderness of our very souls, like our Christian fathers and mothers of the desert and the desert-sea, opening ourselves to transformation by being led by the Spirit. The Spirit of God calls us from the noise of our everyday lives, that noise that has such a firm hold over all of us, the noise of wild beasts. These wild beasts within us being shepherded by Satan into confusion and darkness: pushed and pulled by every fleeting desire or whim, unstable like being on the deck of a ship during a storm.

The promise of baptism states that Christ will not come to us, but that, through the waters, He is already within us. We are the Ark, our flesh is the tabernacle carrying the unity of the promise and the Spirit in our souls, the unity of Jesus Christ.

The early Christian monastics understood this and sought to bring Christ to the demons… We live in a different time. The enemy-occupied territory no longer lies outside the walls of Egypt or off the coast of Scotland, but dwells within us. The enemy-occupied territory is all around us, which should not inspire despair, but even more hope that wherever we find ourselves, God is there, too.

That is the promise made to Noah and every living creature. We have no reason to fear what we might find in our own deserts: what lies beneath the surface of overeating, for instance? What lies beneath the surface of our frustrations on the road when the person in front of us is going two miles below the speed limit? What lies beneath the surface of our own insecurities in relationship or finances?

Do not be afraid, go into them, follow them to their roots.

The fasting of Lent is meant to quiet the ways in which we, unaware, cut ourselves off from God. It is meant to draw us into the desert and confront the wild beasts that live within, that are led by the passions, that are shepherded by Satan, living in a prison of their own making. These wild beasts, perhaps, are the first aspects that reveal themselves when we begin to get quiet, when we become less, when the flood waters recede. Perhaps, instead of appeasing them we can be like Christ and listen. The wild beasts are not something to cut off, to destroy, but as God sees them, they are worth saving, they are worth redeeming, and they are worth dying for.

So, listen to them. They are telling us something, all of us. If God felt that they were worth dying for then they must have some use to Him. Lent is a good time to sit with them, waiting with and alongside the angels, letting them tell us how they might be used, letting them tell us how they came to be, and letting them tell us who we are deep down, far below the still waters of the desert. Christ will not abandon us, He is making us His, and that includes all of us, and the promise of God lets us know that by finding the quiet spaces within us He will fill in that space with His light, that we might be jointly-known, and well pleasing to Him.

Almighty God, whose blessed Son was led by the Spirit to be tempted by Satan: Come quickly to help us who are assaulted by many temptations, and, as you know the weaknesses of each of us, let each one find you mighty to save; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Si comprehendis, non est Deus