Behold the maidservant of the Lord!

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has looked with favor on the lowly state of his servant.

Surely from now on all generations will call me blessed,

for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name” (Luke 1:46-49).

The Western Rite observes Advent which begins at the end of November this year while in the East the Orthodox Church observes a period of fasting for forty days, starting today, leading up to the Nativity of Jesus Christ, on December 25th. Thematically, the West focuses on the birth of Christ, the faithful receiving His grace, and His Parousia.

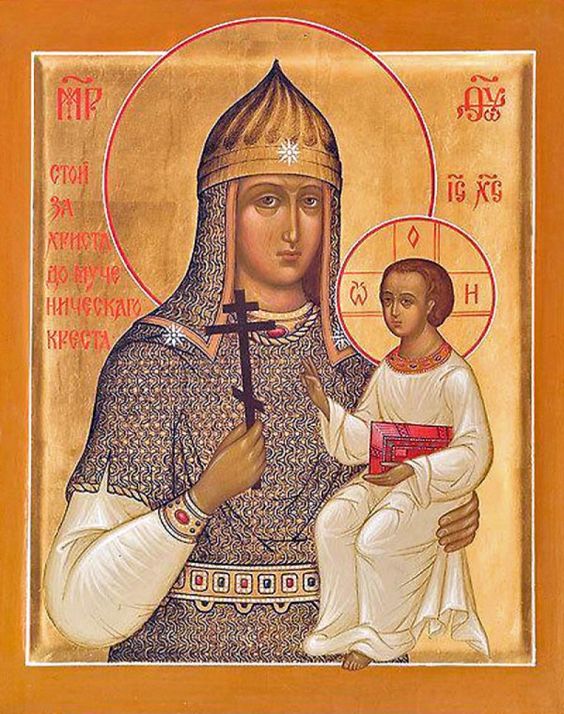

The East focuses centrally on the proclamation and glorification of the Incarnation of God. There is no reason that one preclude the other, however the latter focus enables us to step into the life of the Theotokos by taking on the podvig (подвиг) of fasting.

The podvig is a Russian term which has no one-to-one translation in English, but essentially it means spiritual struggle, but as a verb. We perform a podvig.

We take on a podvig because it is easy to grow complacent in the materialistic culture that is like the water that we swim in; the podvig shakes up our spiritual practice, adds discomfort where once there was contentment, and reorients our focus on God. The podvig is like a cross in which we crucify ourselves, dying to the self, and letting the Spirit of God grow in resurrection.

In the spirit of the Divine Feminine, the podvig is akin to the martyrdom of motherhood: fasting is making room for Life to grow from within us, God becoming Incarnate through our sacrifice.

There is always sacrifice in relationship; taking on a podvig means we are acknowledging that we will be asked to give things up: our whole life. The podvig of the Christian life is a war after all. St. Ephraim of Katounakia said, “Man, as long as he lives, must always struggle. And his first fight is to defeat himself.”

The Blessed Mother is our window into the one who has defeated themselves, displaying a grace that is awe-inspiring. The Theotokos is the embodiment of meekness. A term that has lost favor in recent decades as its meaning became closely associated with a pushover, rather than one whom has achieved a spiritual mastery of self. The podvig is the “spiritual struggle of bringing the soul into mastery over the body” (podvig, orthodoxinfo.com). Furthermore, the podvig is done in the service of something; it is a sacrifice we take on to bear spiritual fruit. It is not done for our sole edification, but for many.

Meekness comes from the Greek word πρᾳΰτης (prautes), a feminine noun emphasizing gentle strength, a disciplined calm, and a composed attitude. It is like Tai Chi push-hands, finding the way to use the smallest amount of force for the greatest effect. Moreover, the Hebrew עָנָו, a masculine noun, meaning how much one is able to endure:

“A great example of someone who lived this virtue was Moses, who was the meekest man to ever live. For instance, Moses never complained to God about the grief Miriam and Aaron caused him. He simply choose to bear the burden. Moses’ meek disposition was also evident in Exodus when he was literally wearing himself out trying to help everyone solve their problems. In spite of this, he never complained or even gave thought to how it could affect him personally. Hence, Moses’ meekness wasn’t a character of timidity or letting other people run over him. On the contrast, it was a powerful demonstration of disciplined strength beyond what most people could endure” (Mark Caner, Spiritual Meekness).

So, meekness melds into a balanced yin and yang virtuous quality of an enduring and determined individual, meeting every challenge with a silent strength.

Let it be done unto me according to your word.

Practically, the fast is an opportunity to cultivate spaciousness within ourselves, seeking silence, and being with God.

Silence is the way for us to get over ourselves (which is real magic) and not need to be in the spotlight; we do not need to react from our ego, pride, or vainglory. We act out of love: patience, kindness, radical listening… This is why we must conquer ourselves first, otherwise we continue holding subtle and unconscious factors within that are easily manipulated and reactive; we become tempted, falling prey to the schemes of demons, or: Falling prey to dealing malevolently with those around us.

This means prostrations, almsgiving, and fasting. Fasting is a physical embodiment of the silence that allow us to combat our passions, be with God, and—by His grace, cultivate His Spirit within us, becoming “God-bearers” like the Blessed Mother. Much more than keeping a strict diet the fast invites us to find ways in which we are severing our connection with God, where we are full of ourselves instead of confronting the present moment with the disciplined calm of meekness.

There are mental blocks that we put on ourselves which disable us from opening our hearts to God. We have ways to hide ourselves from Him using legalism, guilt, and fear from giving ourselves to Him. The real meaning of the word sin points at the spiritual blocks that we have within us that keep us away from God. The podvig is an aspect of arms we take up to rid ourselves of these blocks.

Sun Tzu wrote, “A victorious army tires to create conditions for victory before seeking battle.” The podvig is not the victory but the battle; the conditions in which we enter the life of the Theotokos and endeavor to cultivate Christ within us is embodying the eternal love of God that is sought in still silence, because silence—like God—is eternal.

Sin in the above case is like resistance to change… Instead of creating the necessary conditions in which change can occur one strives to run away from the spiritual struggle, rather devoting themselves to the timidity that the culture fasley assumes to be the defining quality of meekness. Where we declare that the conditions are, in fact, not right for the battle, hoping they will change so that we do not have to. The externals may change, but the conditions never do, because resistance (generally) comes from within.

It is the faculty of mind that clings to the passions, to fear, to hate, and to pride.

Though God says, “See, I am making all things new,” we are habituated to being resistant to change. We would choose our familiar chaos over the unknown heaven that awaits us, which is the purpose of cultivating silence. It can be frightening to step into the shoes of the Blessed Theotokos who was asked by God to change the world. The Virgin helped initiate the re-ordering of the cosmos, bringing forth God made flesh from her womb, “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth” (Matthew 5:5).

That is what all mothers do, by the way, they reorganize the fabric of reality by bringing life into the world.

Stepping into the shoes of the first apostle, Mary, we must steel ourselves knowing that God will ask things of us, too. A relationship with Him requires us to be open and listen to the Blessed Mother when she instructs us, “Do whatever he tells you” (John 2:5).

The podvig of fasting is striving to open the channels of communication between us and God, attaining space and silence where there was once noise, passions, and food blocking our ability to hear and respond: Let it be done unto me according to thy word… This is the way to respond to God, the way that one who has defeated himself responds, one whose soul has mastered their body.

So, we begin this Nativity Fast with our intention to become like Christ through Mary, embodying the spirit of meekness she so beautifully exhibited by our own meeting the passions, the demons, and God Himself with silence.

Blessed are the meek, for they will bear Christ. Selah.

Si comprehendis, non est Deus