Egalitarianism, revelation, and in-fighting

“You worship a Being who eludes your consciousness. Our divine service is at one with our conscious awareness. That is why salvation for mankind had to be prepared among the Jews. The hour will come, and it has come, when the true worshippers of God will worship the Father with the power of the Spirit and in awareness of the truth. And the Father yearns for those who worship HIM in such a way. God is Spirit, and those who worship HIM must do so with the power of the Spirit and in awareness of the truth” (John 4:22-24).

The Hebrew Bible was written during a time that a stratified social sphere favored a patriarchal model with its language mirroring the same therefore the Hebrew Bible, the basis of the Jewish faith and what bore the Christian tradition has an inherently masculine bent making the feminine figures in the text no less important, but somewhat sidestepped portraying the Hebrew peoples’ as children of the three patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (later Israel).

This era of the Bible, the narratives taking place in the Book of Genesis, is known as the patriarchal age. The academic consensus on the historicity of this age has grown increasingly dim with most modern scholars asserting that, even if there is evidence that supports the existence of the patriarchs, there is not much hope in recovering such records. An academic evaluation of the texts does, however, maintain that they are an accurate reflection of the second millennium BCE.

The accuracy of the age presented in Scripture is important due to the radical initiative taken by the New Testament in portraying the feminine figures as, no longer side characters or powerful oracles, but rather critical to the ministry of Jesus Christ.

During the Apostolic Age and in the centuries following it before the adoption of Christianity by Rome there were religious sects, inspired by the Christian thought, which aimed at an egalitarian model for community with women having an equal footing with men in the social construct and even within religious practice. The basis of which comes from Scripture, and one does not need a working knowledge of koine Greek to appreciate that it was the women who stayed with Christ during His death on the cross while the disciples ran away in fear. It was a woman who was first illuminated to the risen Christ, and it was this woman, St. Mary Magdalene, who was the first person to preach the good news of our resurrected Lord.

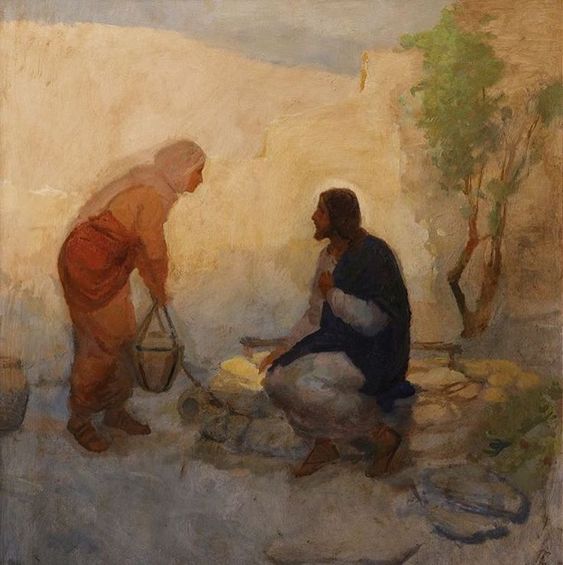

The Samaritan woman at the well fits into the ministry of Christ in much the same way, as a living witness to the Messiah, causing others to believe in Him—causing others in Samaria to go to Him. She is venerated in the Eastern Orthodox tradition as St. Φωτεινή (Photine), which means luminous one. Her spreading the gospel and causing others to go to Christ have brought many Christians to recognize her as an “equal to the apostles.” This is a special title amongst saints and shows her eminence in Jesus’ ministry and His followers’ lives.

In the case of both Sts. Mary and Φωτεινή they come face-to-face with Christ and though we can extrapolate a metaphorical message from the texts inferring it is the feminine principle at work within us all that comes into the presence of God. The energies of God penetrate us through our surrendering, meekness, and softness but this interpretation should not be so wrapped in a psycho-spiritual lens that it narrows our ability to see women preaching the good news in scripture. Therefore, the communities cropping up in the early days of the Church have their foundation in Christ Jesus.

Perhaps one of the most frustrating examples of what the canonization process under a Roman Empire took from the Christian tradition was the designation of the Gospel of Mary as apocrypha. While its “gospel” classification may be incorrect as its contents do not encompass a biography of Jesus’ life as the others do. The Gospel of Mary is focused on revelation and salvation through the believer returning to God and liberating themselves from the things of this world; it also implies direct revelation with God comes from a purifying of the faculty of the mind and soul known as the νοῦς (nous). The former and latter constitute a mystical approach that is not Gnostic, which the text is erroneously categorized as, but is a basic foundation for Christian spiritual thought—found most readily in writings associated with Eastern Orthodox traditions.

The Gospel of Mary is an important document in the early Church as it contains instructions for θέωσις (theosis), and it presents echoes of the patriarchal age within the text while trying to convey a vision of Christianity that was moving away from this relic of the second millennium:

“Peter answered and said the same thing. He challenged them about the Savior: ‘Did he really speak with a woman without us knowing it? And in secret? Are we now supposed to change direction, and all be taught by her? Did he prefer her to us?’

At this Mary cried and said to Peter, ‘My brother Peter, what is it you suppose? Do you think I made this up in my imagination? Are you accusing me of lying about the Savior?’

Levi answered, saying to Peter, ‘Peter, you have always been a hot-head. Now I am watching you fight against the women as if they were our enemies. But if the Savior himself made her worthy, who are you, really, to dismiss her? Surely the Savior knows her quite well. After all, he loved her more than us!’” (Gospel of Mary 9:3-8).

This text may illustrate a true event between the apostles, however what it is referencing is the historical struggle within the early Church between its ties to its patriarchal genesis and what the Church was called to look like in light of the Resurrected Christ. The tensions between an ecclesia based on an old model or a hierarchical structure that was inclusive to believers following St. Paul’s words: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28).

The tensions between the outdated model of exclusive, patriarchal overtones and the more dynamic, inclusive ecclesia are ongoing, and while there is record to show this conflict’s origin the Gospel of Mary’s dating puts this in-fighting as occurring as early as the late first century and no later than the early second century CE. The issue this raises is related to the structure of the proto-orthodox Church.

If we are going to believe the doctrines put forth by groups such as Churches of Christ then we can, reasonably, date the inception of Christianity not at Pentecost, but at the canonization of the New Testament in the years following Council of Carthage’s Synod of 397 CE, this is strictly when the ratification of the Bible, both Hebrew and New Testament was declared in the Church while the canon was unofficially recorded through a Festal Letter, written by the Church Father, Athanasius the Great in 367 CE.

Regardless, the Churches of Christ—if they are the true church—can trace their lineage back to the third century at the earliest.

Proto-orthodox Christianity is a term describing the larger Christian movement in the first and second centuries during its formative years codifying its belief and combating heresies such as docetism, adoptionism, and Arianism. The proto-orthodox Church saw a time of validating doctrine that would go on to define the Christian religion. This involved apostolic succession, a hierarchical structure: bishops, priests, and deacons, alongside the aforementioned opposition against heretical belief.

The Didache, a treatise written presumably in the first century with some scholars arguing its writing occurred in the second, was an important document in the burgeoning Church. This document outlined the Church’s oldest example of a catechism presenting baptism by immersion (or sprinkling if water is unavailable/impractical), the Eucharist, and fasting (taking place on Wednesdays and Fridays) as integral to Church life.

The Didache goes on to include the Church organization during this early stage of proto-orthodoxy, affirming bishops and deacons’ positions as authoritative with priests serving to celebrate the Eucharist. This text is considered to be a part of the Apostolic tradition as it was written in the era of Church Fathers who were themselves disciples of the twelve disciples. The import of this text is seen with some of those same Church Fathers regarding the Didache as a part of the New Testament while being rejected, finally, as non-canonical.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church does include the Didache in its canon.

Now, this is a long way of demonstrating that Church structure was already well-defined before the adoption of Christianity as Rome’s state religion.

This is also meant to illustrate how the Church’s structure was never decentralized or non-hierarchical—the normative model that the Churches of Christ want the Christian Church to be restored to is exemplified by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The only evidence we have currently of the loose organization reminiscent of what the Churches of Christ envision as the true Church is seen in the various Christian sects that were eventually trampled down by unification of the Church in the third century—under the banner of Rome.

These sects traditionally are referred to as Ebionites, Gnostics, and Marcionites. And I say traditionally because under the umbrella of “Gnosticism” there are a lot of different schools of thought without mentioning the fact that all of these sects overlap in some form or another.

The final reason a text like the Didache is important is that its inclusion in tradition demonstrates that not all non-canonical texts, or apocrypha, are created equally and just because a text is not included in Scripture does not necessarily bar its inclusion within Church life. Taking this into account we can re-evaluate the text that challenges our modern concept of unanimity in the early proto-orthodox church.

To reiterate, The Gospel of Mary, is erroneously interpreted as a Gnostic text because its contents are monistic while Gnostic texts typically follow a dualistic cosmology. The Gospel of Mary’s purpose is to address conflicts within the Church, it offers us a rather convincing argument in favor of the legitimacy of women in leadership roles within the Church, and the validity of post-resurrection revelation. The latter of which is spiritually tenable due to the life and epistles of St. Paul, which will be addressed later. The Gospel of Mary is a first century text—a second-generational treatise coinciding with the writings of the Apostolic Fathers—that ultimately denounces illegitimate power, the traditions of men, and challenges the authority established in the patriarchal age.

And it is this writer’s opinion that that is exactly what Christianity aimed to do. If we want to use Scripture as our sole authority then it is not much clearer than in Christ’s rebuking of spiritual teachers:

“He said to them, ‘It was about you, you hypocrites, that Isaiah prophesied a true word:

Only with their lips do men honour me,

Their heart is far from me,

They try to serve me with empty forms,

Their teaching is empty of all but human notions and doctrines.

‘You abandon the aims of God, all the more to cling to the human traditions which prescribe for you the washing of jugs and chalices and many other such things’” (Mark 7:6-8).

It may be apocrypha, it may be non-canonical, but to call the Gospel of Mary anything other than following in the tradition as given by our Lord, Jesus Christ is to deny the essence of its content and that is… nigh unforgivable.

But see, the point wasn’t establishing a vision of spiritual perfection as given in the “Gnostic” text, the point was not to confront first and second century contentions within the early church, nor was the point in facilitating the means for the individual to follow the Way of Christ. The point, by the third century CE, was to unify an expanding nation under a central banner and authority. That authority would be a codified Christian religion which would establish the Church and its place in the Roman geopolitical landscape.

And by way of Rome—the world.

Furthermore, the Gospel of Mary being categorized as Gnostic literature can be seen as a proto-orthodox means of discrediting the text by the third century, with the Gospel, to reiterate, pointing to Christian tensions within the larger schema of Christian thought during the second century. This move against the gospel is indicative of a pattern of the proto-orthodox church to discredit texts and persons who stood against the precursor movement of Christian orthodoxy.

In the next post we will focus our attention on Marcion of Sinope, who could quite possibly be the patron saint of the revisionist movement. The restorationist approach to Christianity that rose to prominence during the Second Great Awakening in the United States which was the breeding ground for the Churches of Christ and their want to unify Christians into a single body that is modeled after the original church and so, too, did Marcion of Sinope.

Si comprehendis, non est Deus